|

RELIGION AND DEMOCRACY: AN EXCHANGE OF EXPERIENCES BETWEEN EAST AND WESTTHE CESNUR 2003 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE |

Nationalism, Religion and The Muslim-Christian Relationship:

Teaching Ethics and Values in Egyptian Schools

by Johanna Pink, University of Tuebingen

A paper presented at the CESNUR 2003 Conference, Vilnius, Lithuania. Preliminary version. Do not reproduce or quote without the consent of the author.

Education, and especially religious and value education, is a field that serves well to exemplify the role of religion in a state. Some states will have no religious education at all; some will have denominational religious education; some will have multi-faith curricula, or they will teach ethics or philosophy rather than religion. The way in which faith and values are taught in schools reflects a certain attitude towards religion and ethics, and it also serves to multiply this attitude.

Education, and especially religious and value education, is a field that serves well to exemplify the role of religion in a state. Some states will have no religious education at all; some will have denominational religious education; some will have multi-faith curricula, or they will teach ethics or philosophy rather than religion. The way in which faith and values are taught in schools reflects a certain attitude towards religion and ethics, and it also serves to multiply this attitude.

Like in most Muslim countries, in Egypt, religious education is mandatory. Religious education is provided for Muslims and Christians separately. Christians account for probably around 10% of the population; the majority of them are Orthodox Copts, but there are twelve other officially recognized denominations. Following Islamic law, Egyptian law recognizes Islam, Christianity and Judaism as revealed religions whose religious laws are applied in matters of personal status and who enjoy the protection of the state. As there are only a few hundred Jews left, most of them old, the question of Jewish religious education is obsolete. Other religious minorities, like Baha‘is or Jehovah‘s Witnesses, enjoy no protection and have no legal status. According to government statistics, there simply are no adherents of these faiths in Egypt, so the question of religious education is naturally not discussed with regard to them - in spite of the fact that there are probably several thousand Baha‘is and at least as many Jehovah‘s Witnesses in the country, which are not small numbers for a country like Egypt where new religious communities enjoy no protection and are supposedly non-existent.

The main framework in which the debate on religious education takes place is the Islamist-secularist controversy on the one hand and the problematic relationship between Copts and Muslims on the other hand.

There has been Islamist pressure on the government for more than two decades now. The government has responded by repressing political Islamism, but at the same time partly fulfilling popular Islamist demands. In the educational sector, however, government policy has tended towards marginalizing religion. This is partly due to the fact that it was exactly the educational sector where Islamism developed into a political force in the 1970s. The Ministry of Education is often under attack from Islamist and conservative Members of the Parliament because the number of religious education lessons in schools is relatively low, especially in the secondary schools, and because the marks are not relevant for exams.

Another sensitive issue in the field of education is the relationship between Muslims and Copts. After several incidents of violence between Christians and Muslims, there has been a debate on the reasons for the apparent tensions. The general tendency has been to downplay the incidents and to emphasize the peaceful coexistence of Muslims and Copts. Copts often are reluctant to complain about their situation - they usually prefer to play the nationalist card and stress the unity of the Egyptian people and to claim that there are no differences between Muslims and Copts.

Another sensitive issue in the field of education is the relationship between Muslims and Copts. After several incidents of violence between Christians and Muslims, there has been a debate on the reasons for the apparent tensions. The general tendency has been to downplay the incidents and to emphasize the peaceful coexistence of Muslims and Copts. Copts often are reluctant to complain about their situation - they usually prefer to play the nationalist card and stress the unity of the Egyptian people and to claim that there are no differences between Muslims and Copts.

Still, as far as the educational sector is concerned, there have been complaints, especially from secular and human rights oriented institutions, that Coptic history and culture are grossly underrepresented in the curricula, or not represented at all. Besides, knowledge of the other faith is not part of the religious education curricula. Critics say that it is difficult for pupils to value tolerance under these circumstances. The debate is tense, because in Egypt, pointing to discrimination of religious minorities is often understood as undermining national unity. The argument is that all Egyptians are equal, that there are no divergent interests and thus there is no need for anti-discrimination measures. Many Copts support this position, as historically, the Coptic community has embraced nationalism as a way to escape the religious inequality of former times. However, today‘s brand of nationalist political correctness, where it is not allowed to even use the words "minority" or "pluralism", often just serves to discourage attempts at uncovering religious discrimination or structural inequality.

In 1999, the secular and human rights oriented Ibn Khaldun Center for Development Studies submitted a proposal for the reform of several curricula, including Christian and Islamic religious education, Arabic, history and social studies. The project was called "Making Egyptian Education Minority Sensitive" and aimed at teaching pupils to value Coptic culture and history as an integral part of Egyptian history and at stressing values of tolerance and peacefulness in the respective religious education classes. The lessons included texts about Coptic monasteries, famous Coptic personalities and the important role of Copts in the independence movement. The Islamic religious education curriculum proposal emphasized justice, peace and tolerance as central Islamic doctrines, downplayed the importance of religious law and claimed that according to Islamic theology, all righteous believers, not only Muslims, go to heaven. The Christian religious education curriculum proposal also promoted tolerance and stressed the role of Christians in Egyptian society. Furthermore, there was a lesson intended for the social studies curriculum about citizens‘ rights and the patriotic duty of democratic participation.

It seems as if the Ministry of Education had been in favor of the project in the beginning, but when it was finally published and received a lot of public criticism, the ministry hastily distanced itself from Ibn Khaldun Center. The Center had possibly made a strategic mistake in appointing Ahmad Subhi Mansur as responsible for the religious education part. Ahmad Subhi Mansur is a theologian who had to leave the Azhar university in 1988 when he had published his ideas on basing Islamic theology solely on the Qur‘an. He dismissed the prophetic traditions and thus much of classical Islamic law. Consequently, he is considered an apostate by most Egyptian theologians. After the Ibn Khaldun Center had published its proposal, criticism at first addressed the minority question, but soon it centered exclusively on the Muslim religious education part of the proposal, and the average newspaper reader had to get the impression that the project consisted of nothing else than this religious education part and was an attempt at distorting Islamic theology. There were parliamentary hearings, the project was the target of a lot of hostility, and in the end it was brushed off. Several months later, though, some newspapers published an inconspicuous piece about a committee that was being formed in order to revise the representation of Coptic history and culture in the curricula.

Another, more remarkable development was that quite surprisingly, the Ministry of Education introduced a mandatory ethics class for the first three grades of primary school in the school year 2002/03, called "morals and values education". The amount of religious education classes - three hours per week at primary level - has not been reduced for the moment being, though Islamists have voiced fears that religious education will suffer from the introduction of ethics lessons.

Not surprisingly, this new ethics class was criticized both in Parliament and in the press, though apparently not as heavily as the Ibn Khaldun project had been attacked. The Parliament‘s committee for education called on the Minister of Education and questioned him about the purpose of the new subject. Critics argued that ethics cannot be separated from religion, which they say the new subject does, because it does not teach ethics from the perspective of a particular religion, and teaches Muslims and Christians together. Islamists argue that pupils are going to lose their identity, that they are going to be confused and lose all sense of morals as a result. Obviously, the Ministry of Education was apprehensive to a certain degree about how the project would be received, because unlike other school books, the ethics books do not reveal the names of the authors.

A representative of the Ministry of Education said in front of the parliamentary committee that the purpose of the new ethics class was to raise a generation that is able to stand up to Bush and Sharon.

This is an ambitious and, of course, very political aim. The question is, what kind of values is the Ministry trying to teach to its pupils in order to achieve this goal? And what role does religion really play in the ethics classes? These questions are particularly interesting because ethics classes doubtlessly exemplify the ministry‘s view of what kind of citizens Egyptian children should become much more clearly than religious education classes. Religious education classes are mainly developed by representatives of the respective religious communities, whereas in the ethics classes, the ministry implemented its own ideas.

During a short research stay in Egypt, I have obtained the textbooks for the ethics classes that are published by the Ministry of Education and are to be used by all state schools. There is one per term, and there are two terms per school-year, thus all in all, there are six textbooks. They are rather cheaply produced and are intended for use by one pupil only - in the next school-year, there will be new ones. Contents may change from year to year. They probably will in this case, because now the textbooks for the second and third grade rely on the fact that the pupils have not had ethics education before, thus they cover the same topics as the books for the first grade, only on a higher level.

There are six to eight topics per term. They are, in the order in which they are treated: 1. Cleanliness, hygiene and environment; 2. honesty; 3. cooperation; 4. responsibility; 5. love; 6. sense of beauty and of order; 7. only in third grade: modesty; 8. freedom; 9. happiness; 10. unity; 11. peace; 12. belonging; 13. economy; 14. respect; and 15. only in second and third grade: tolerance.

These are, of course, very broad topics. What values do the ethics lessons convey through these topics?

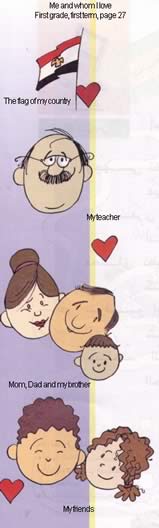

One of the first and foremost values that is promoted in the textbooks is patriotism. This includes a lesson for first-graders about love, in which there is a row of pictures of possible - or recommended - objects of love in the following order: "The flag of my country - my teacher - Mom, Dad and my brother - my friends". Part of the lessons on patriotism is that the textbooks try to promote a feeling of unity between all Egyptians - Muslims and Christians. It is stressed that love of the motherland extends to all people living there, Christians and Muslims. In many stories, children with Muslim names have friends with Christian names; the stories start, for example, with phrases like "Ahmad and Girgis go swimming", or "Ali, Georges and Zainab are friends."

One of the first and foremost values that is promoted in the textbooks is patriotism. This includes a lesson for first-graders about love, in which there is a row of pictures of possible - or recommended - objects of love in the following order: "The flag of my country - my teacher - Mom, Dad and my brother - my friends". Part of the lessons on patriotism is that the textbooks try to promote a feeling of unity between all Egyptians - Muslims and Christians. It is stressed that love of the motherland extends to all people living there, Christians and Muslims. In many stories, children with Muslim names have friends with Christian names; the stories start, for example, with phrases like "Ahmad and Girgis go swimming", or "Ali, Georges and Zainab are friends."

Two further things are striking.

First, the value of freedom, though a topic of its own, is consistently subordinated to values like responsibility, fulfilling one‘s duty, belonging and respect. The textbooks contain phrases like "You have the right to be free, under the condition that you fulfill your duties." Thus, the system of values is essentially anti-individualistic.

Second, the textbooks describe an ideal of development that is aimed at achieving a Western life-style, and quite different from the reality of life that most Egyptians experience. One lesson propagates limiting the number of children to three. Several lessons tell children to collect rubbish that pollutes the streets, to avoid noise, not to eat food from street vendors, etc. The model families shown in the books usually have two or three children, a middle-class life-style and wear Western clothing - very few headscarves can be seen. All this stands somehow in conflict with the daily life of most of the pupils. Whoever knows Cairo can imagine that the task of picking up the rubbish in the streets is illusionary, and that children‘s noise is far from being the main reason for noise pollution. There is only one rural scene shown in the whole series of books - in a lesson about patriotism. Obviously the government has the goal of teaching the youth some virtues that will help the government‘s agenda of development in the sense of achieving a Western lifestyle - without necessarily adopting Western values like freedom or democratic participation.

Religion is not completely absent from the textbooks. There are frequent references to God as the creator of earth and creatures, for example in the context of protecting the environment. One lesson stresses that God loves diligence and fulfilling one‘s duties. It is also stated several times that religions promote peace, which seems to be mainly meant as an appeal for religious tolerance between Christians and Muslims. Religious pluralism is depicted more or less as a given fact - the possibility of choosing one‘s religion is not addressed. In all the instances where religion is referred to, the impression prevails that religion is instrumentalised to emphasize the intended message. The message is certainly not derived from religious sources. Religion is rather used as a tool to underline the merit of certain types of behavior.

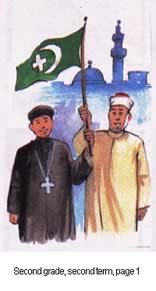

There are few references to specific religious beliefs. A list of holidays lists national as well as Muslim and Christian holidays. Two stories imply Muslim prayer rites. A picture shows a child building a mosque out of building bricks. And when Jesus is mentioned - as an example for a person who promoted peace - the textbook uses the Muslim name "'Isa" instead of the Christian name "Yasu‘". But mostly, religion is either referred to in a very general way, or reference is made to both Islam and Christianity. For example, there is a picture of a Muslim Imam and a Coptic priest holding a flag together that shows a crescent and a cross.

All in all, religion is depicted as a general source of values, but not the primary one - patriotism and the wish for development play a far more important role. The textbooks don‘t want to promote religiosity, they rather take it for granted. Often, religiosity appears just as a part of national culture - there are Christians, there are Muslims, that‘s the way it is, and they should get along.

It is nationality, not religion, that is considered the main source of identity in these textbooks. Peace and tolerance between Muslims and Christians are promoted. In this way, the introduction of ethics classes picked up on some of the demands the Ibn Khaldun Center had made in 1999. The Ministry, however, chose to promote its agenda not by addressing the conflicts between the religions, but rather by denying the existence of such conflicts, which is about the direction the whole public debate is taking. The Ministry also chose not to adopt Ibn Khaldun Center‘s proposed lesson on citizens‘ rights and political participation as a patriotic duty.

All in all, with the strong promotion of nationalism and development and with the emphasis of duty over rights, it seems that the new subject of morals and values education is completely in line with the interests of an authoritarian national state.