CESNUR - Centro Studi sulle Nuove Religioni diretto da Massimo Introvigne

www.cesnur.org

www.cesnur.org

Abstract

Adapting a famous Weberian metaphor, we explore cultural dimensions of the recent social uprising in Morocco. The uprising has ushered in modest political change and some lifting of consciousness, but it has the potential promise of much more to come. The crucial point we make is that no change, institutional or other, takes place in a cultural vacuum except just possibly in wholly revolutionary times— during which old rules, guidelines and meanings no longer apply—which these circumstances are not. Essentially, the new potentials are lived out and experienced in old cultural patterns. In this respect, we examine the role of maraboutic and Islamist cultural forms in the current conjuncture in Morocco. For most subalterns, meaning and action takes place and will take place in and through these local cultural designs, but whether these local traditional cultural structures will crystallize and calcify so as to freeze and reverse progressive developments or mollify and adapt, within their own vectors and logics, to accommodate change and aid a specifically Moroccan coming into modernity is a matter for careful cultural analysis allied with culturally sensitive modes of politics, influence and interventions on the ground. We conclude by examining the activities of the 20th February movement and their use of new media in this context. New revolutionary cultural forces may not be at play in Morocco today but believable counter-hegemonic cultural struggles which could lay the groundwork for really fundamental change are a possibility.

Keywords: Arab Spring, subaltern consciousness, popular culture, popular Islam, media, Islamist minorities, Islamism, fundamentalism, maraboutism, jinn, exorcism, saints, trance dance, religion in practice, ethnography, Morocco, Weber, internet, facebook, the 20th February movement.

Acknowledgements: We would like to warmly thank Philip Hermans from Leuven University, a cultural anthropologist working on Moroccan culture for more than thirty years, for his encouragement and constructive comments on one of the final drafts of the article.

Introduction

In any given society there are always gaps and mismatches between material circumstances, material changes, political conjunctures, cultural forms and practical consciousness. We want to specify this a little more closely in the case of Morocco and its subaltern[1] classes through the adoption and application of a famous metaphor from Weber where he compared culture's role to the role of a railroad switchman. He averred that "not ideas, but material and ideal interests, directly govern men's conduct. Yet, very frequently the 'world images' that have been created by 'ideas' have, like switchmen, determined the tracks along which action has been pushed by the dynamic interest" (1946, p. 280). Weber showed us in The Protestant Ethic of Capitalism how the cultural switchman embodied in religious formulations influenced how people worked, spent their money and organized their economic lives.

We argue that the role of the `switch gear` of the Arab Spring has been underestimated and is complex; Morocco is our example. We see maraboutism and Islamist organizations, as well as conflicts within them, as cultural forms that are crucial sources and frames of meaning during the current social upheavals. Western influenced media and commodity forms are also growing in influence and may be important new centers of switching gear. All can be involved in complex switching operations. Our starting point is that liberal doctrines of emancipation á la western philosophy and practice may be wholly misplaced and certainly cannot be imposed as a guide or framework to these switching operations. The masses in Morocco divide up the world differently. They may not follow desiccated abstract doctrines from the West. There is a cultural migration towards available and palpable local options bedizened with symbol, ritual and sensuality. Options from different repertoires may not be mutually exclusive, groups and individuals may pursue more than one, certainly for example in different compartments of their lives. Eickleman and others suggest all conduct is situational so even some western liberal like notions might pertain in say academic contexts whilst traditional or Islamist ones might pertain in domestic or street contexts. This may be true, but especially now there is the possibility for unexpected and forced collisions on the railway tracks. Collisions mean that some of these life worlds/repertoires may be forced into mutual critique, mutual penetration, mutual invalidation, invalidation of one against another, etc. Similarly `multiple subjectivities` might not survive the concentrations of the `modernity shock`. Cultural forms and the switching gear do not remain in a steady state in moments of crisis. The Marxian critic, Raymond Williams, speaks of situations where there are possibilities of the deconstruction of the dominant ideology during times of exceptional change and creativity. But all of this still runs along cultural tracks of some kind except in the wholly unlikely event of the emergence of a bottom-up new revolutionary culture and mentality. These uprisings are making dramatic changes whose possibilities for daily living arrangements are not yet clear to the people; the political situation may worsen especially since new ideologies are not yet constructed, illiteracy not yet combated and dominant cultural worldviews not yet transcended. At the least, revolutionary movements should evolve their own anti-hegemonic cultures; otherwise they will fall within the grip of the old deep-rooted politico-cultural thought of cooptation, clientelism, patronage with personalized relations merely reproducing them, running along all too familiar cultural tracks.

The Arab revolutions arose as responses to the 'unsettled times' of massive demographic shift and multiple failures in the economic sphere. They started as political revolutions that sought to establish new political systems without an explicit role for cultural meanings, traditional or emergent. The danger is that contemporary political developments are culturally switched into old meanings removing the `con` from contemporary so making them only temporary and producing the experiences of anomie all over again. If cultural awareness and at best innovation does not lead the process from now on there is the danger that unbridgeable gaps will remain between new political institutions and received cultural forms unable to become politically adaptive, especially among the silent majorities untrained in innovative social and cultural practices. The new possibilities may simply run down the old tracks of corruption, segementary structures and fraud. What existing and emergent cultural resources can still be used for genuine switches into an ethics of democracy to be properly internalized by subaltern populations? Is there a scope for a micro cultural switching gear that may be made operational through cultural awareness and self-awareness and may be directable for political purpose?

Multiple Methods

This research draws mainly on ethnography and retro ethnography carried out in various projects and research sites in 2008, 2009 and 2011.[2] Other data sources utilized included public documents, interviews, participatory observations. Public documents included the following: Islamist books, leaflets, booklets, and CDs, local newspapers, and Internet sites such as Lakome, Mamfakinch, Hespress , Scoop, goud, Febrayer and klamkom . One of us, Mohammed Maarouf, undertook participant observation on the local faction of the 20th February movement during its public gatherings, sit-ins and demonstrations in El Jadida from the beginning of the movement's emergence. We argue that real and virtual spaces are not completely separate but rather closely interlaced. Accordingly, virtual spaces granted us the occasion to compare, contrast and expand the type of social interactions that occur in the offline social world. Observation online was conducted by viewing texts and images circulated by the movement; after three months of passive observation, Maarouf, assumed the role of active contributor to the group being studied. Walstrom (2004a and 2004b) uses the term "participant-experiencer" instead of "participant-observer" to characterize the nature of the researcher's role in online settings. This 'experience' continues through a Facebook account created since 2011, through communication that has taken place with at least three hundred members and sympathizers with the 20th February movement, so keeping us real-time abreast of debate, events, digital and offline manifestations.

We nevertheless faced methodological difficulties on account of Moroccan internet users' preference for secrecy because they feared police persecution. Entry into the 20th February movement's groups is not difficult but the networks are diverse and loosely structured, and levels of activism vary widely among participants—needless to say it is also penetrated by Moroccan secret agencies. Official membership of the group was not taken up which carried with it the risk of being shut out as unwanted intruders. Interviews and observations were done with full disclosure of the authors' position as sociological observers. The initial contacts with student members of the movement from Chouaib Doukkali University snowballed into further communication with other activists across several of the movement's networks.

Maraboutic Cultural Forms

Not always in consciously recognised ways, maraboutic structures,[3] cultural symbols and schemas traverse large tracts of Moroccan life. It is a genetic part of their religious culture reinforcing other aspects of their religious sensibility and symbolic cosmology. From the outside this seems to lay foundations for the popular acceptance of authoritarian rule and the successful exercise of power where even apparent resistances may be seen ultimately as merely socially reproductive. But seen from the ethnographic resources of a `bottom up` subaltern perspective, we find surprising seeds of rebellious, alternative and emancipatory perspectives that have actually always been there and might be contained for the moment but which through shocks of the modern might find new political attachments in the great awakening sweeping Morocco. One might say that ,thus far, Moroccan subalterns holding to maraboutic beliefs stumble through life thinking their steps are pre-formed by Fate (al-maktub [the Written]), but in the present conjuncture their stumbling might be revealed to them as stumbling between options determined by secular forces and structured by human hands. Resistance then might take on a more material rather than mystic form enabling transition from a tribal to an institutional mode of thought, from the bond of 'asabiyya (group solidarity) to the institutional bond of law.

In Moroccan tradition, Sultans and saints rank at the top of the hierarchal social structure and are believed to be endowed with hereditary powers transmitted to them by their holy lineage. The authority of sultanic rulers and saints is represented in popular imagination and cultural narrative as a mystic power with non-human attributes. Deep-rooted in popular imagination is the belief that Kings and saints inherit a spiritual force (baraka) that can create miracles and can save people from distress. The figures of the sultan and saint have been held in wonder and awe, also surrounded with taboos and benedictions, and culturally represented as distributing centers of charity. The philanthropic work of these religio-political authorities is part and parcel of the exercise of political power in Morocco. Royal donations did and still do play a binding function cementing the bond of loyalty and faithfulness between the throne and actual or potential beneficiaries. If occasional violence is used to mute an uprising, subalterns may regard it as the expression of an angry Father who decides to curse or punish those who rebel against the hand that feeds.

Historically the cultural soil of resistance to political domination was mostly formed from maraboutic components. Moroccan cities and countryside are littered with marabouts, holy shrines made of the burying grounds of local saints. Subalterns imagined saints as saviours with miraculous powers that could steer the course of their destiny. Unable to gain some measure of control over their own lives, they put their faith in the all-powerful saints to grant them some kind of magical emancipation. In popular imagination, those holy protective figures were conjured up in the image of miracle workers who could burst forth water from the underground, evoke food from nowhere, heal incurable diseases, resurrect the dead, talk to them, walk on sea water, talk to animals and inanimate things, travel outside time, foresee the unknown, abstain from food and drink, know the unlikely spots where the treasures of the earth were to be found. They used these powers to protest on behalf of and lead local subalterns.

The most illustrious example from popular culture concerning saints' protection of land and people is their historical saga of triumph over the Black Sultan (sultan l-khal). The Black Sultan was a symbol of ruling terror and oppression in the popular mind. Historically, it was a nickname given by the 'amma (commoners) to Abu l-Hasan l-Marini or Mulay Ismail due perhaps to their black color. Mulay Ismail was reputed for his repressive arbitrary cruelty and promiscuous liturgies of torture and beheadings in public intended to fill people's hearts with terror (cf. Crapanzano, 1973, p. 35-36). According to the hagiographic tradition, no earthly power could stand his hostility save for the baraka of saints. Al-Haj Thami al-Glawi was a qaid who was also nicknamed the Black Sultan in the Haouz (Pascon, 1984). In 1958, he possessed 12000 ha of land. He had shares in cobalt and manganese mines. He also monopolized the distribution of water in the region of Marrakech, imposing taxes on people and controlling the olive and almond crops commerce (Halim, 2000, p. 146).

Until recently, the binary opposition—saints vs. the Black Sultan—structures the cultural worldview of the maraboutic society. Its legends convey stories of the war between the Black sultan and saints. At bottom, the Black Sultan can be considered to be a mythic symbol, an embodiment of people's fearful attitude towards any Sultan or mandarin whose authority was oppressive in the history of Morocco. In cultural narrative, it is stressed that saints defeat the Black Sultan, which signifies that his power is profane whereas the baraka of saints derives from God's immeasurable sacred power that can bring justice to earth, in a sense a political expression of sainthood whose historical roots we can still trace in Moroccan saints' legends and maraboutic practices. It is narrated for instance that Sidi Mas'oud Ben Hsin, a saint in Doukkala, aborted the Sultan l-Khal's attack by hurling against him swarms of bees and gadflies. Ben Yeffu, another saint in the same region, forced the Black Sultan to submit to his power by the help of a multi-headed jinni. A popular version of the legend narrated by some shurfa from Duwar al-Kudya in al-Gharbiya area goes that Ben Yeffu went out to face the Sultan l-Khal accompanied with a black jinni with seven heads. In a challenging confrontation between the two, the sultan commanded his army to catch the saint while the latter ordered his servant jinni to topple the Sultan from his horse and lift him to the sky. The jinni did as he was enjoined, and the Sultan cried tslim (an expression of surrender) at which the saint ordered the jinni to set him back upon his horse, upon which the Sultan quickly fled. Such legends of saints' triumph over the 'Black Sultan' have multiplied in various historical guises over a very long period. In their hagiographies, saints always emerged as justicers defending the meek.

The social fact is that Moroccans followed saints[4] and were recruited in their armies to fight liberation wars. Overrating the baraka of saints was an incentive to the subalterns to stand their ground against oppression and not to give up the fight. Maraboutic belonging was a socially accepted channel of exorcising one's fears and anxieties about social injustice, if not in political expression, through ritual pantomimes, evictions and dances that seemed to symbolically re-enact the ruler's killings and tortures in order to domesticate them. We argue that these emotional bonds and forces can be transferred to new social formations allied to by more overt resistance as the symbol of saint declines in power. The intifada of Beni Bouayache in the Rif in 2012 evinces how the traditional reservoirs of resistance may somehow coalesce with the new wave turning over the cultural soil in Morocco. The death of Kamal l-Hassani, one of the graduate unemployed activists, turned him into a symbolic hero and ever since the town has been a boiling cauldron of sporadic protests, sit-ins and demonstrations despite citizens' exposure to severe detentions and repressions. Another recent example is the sudden appearance of combative Salafist cells in l-Fnidiq, the black market that mainly trades in smuggled goods from Spain, focused on encouraging Salafi militants and new recruits saturated with the combative ideology of Jihad to undertake suicide attempts in Syria (see Rouhi, 2012, October 27).

The maraboutic scene today in the many continuing holy maraboutic shrines still appears to be immersed in saintly chants, dances and perfumes. Maraboutic rituals are intended to fulfil individual needs, especially psychological and emotional needs producing comfort, hope and relief from despair. They also respond to the immediate needs of society by trying to answer to problems of sickness and distress and maintain social cohesion. Folk music thrives with a plethora of maraboutic spirits and tunes evoked in ecstatic trance dances (hadras) and jinn evictions. The epistemic foundations of these practices are bizarre to the schooled who rationalize things in terms of material empirical beliefs and seem to be mystifying rather than mystic, serving finally only social and political obfuscation. But we argue that the surviving and still-working culture of possession and maraboutism may indeed shed light on what most Moroccans feel towards the current political and economic order and how they may resist political domination and economic injuries. Deep down in their cultural logics, possession rituals and trance dancing can be understood as a form of cultural resistance against domination. There are many strands to our argument. Theoretically speaking, spirit possession presupposes the permeability of the body; powerful external forces which could not be assimilated in their abstract forms enter as divinities, ancestors, ghosts, jinns, that have a hold on the body. They are still seen as separate and distinct— certainly detachable—from the body, ethnically alien and foreign to the group. But they are somehow known and capable of some bidding and exist within a daily realm. We argue that this is a way of sensing other incomprehensibly large and abstract forces which cannot be named directly in local cultural and concrete terms. We argue that there are challenging forms here suitable for transplant to modern dilemmas in this mystic soil. For instance, the spectral court assembled during jinn eviction is at least a court—more than most Moroccans get in normal social life for the many economic injuries to which they are subject. With possession at least the human hosts stand in some equal capacity with a personalized, in the same scope as the present body, if still incomprehensible force. This is not the crushing of insects without human colour and imagination. If not controlling their fate, at least in an unlikely swallowing, there is a condensation of outlandish and truly frightening structured forces into the more amiable personification of the jinn, mischievous, answering back and at least partly controllable. The ingestion of wider social forces as an internal habitation at least recognizes the importance of a human scaling of impersonal forces. Further, the dual occupation of the body at least opens up, practically if not philosophically, just what the `autonomous` subject is supposed to be and to whose tune or to what discourse it is supposed to dance, all closed matters in the dominant register of how subalterns are supposed to comport themselves.

The trance dance is a strange spiritual-cum-structural cultural hybrid which in its concrete but simultaneously spectral performances show the forgiven self in mystic jerking communion with the universal powers of Fate rendered in aesthetic human as well as occult ways. Let us not forget the upwards and collective generation of much of the forms: the asymmetrical rhythms of the more violent trance dances come not from the shurfa (noble lineage of the Prophet) but from and express the wider feelings of the grass roots maraboutic community (commoners). Trance dances show tension with, rather than annihilation from, the freight of history. This religio-cultural aesthetic grappling with unknown powers shows that Moroccans have never capitulated, in practice and imagination, to unmediated political and economic power. Of course this cultural mode of resistance spins in a vortex of authoritarian relations fixed up in a priori ways by the maraboutic establishment. Counter-hegemonic aspects of trance dances and jinn evictions prevail but subalterns cannot through them escape their social position though they can sometimes escape the conventions that go with it. They can somehow be free at a symbolic level, transgress and be outrageous and throw out the norms at least for a while. Of course this can also be seen as a `ruse of power` to licence a blowing off of steam, but those alternative meanings remain latent all the time and may be raised anew under appropriate socio-political conditions. Ecstatic religion has kept seeds alive that can be sown anew on different soil. So far, authoritarian hegemony in Morocco universalizes its needs and interests as the interests of society as a whole and most subalterns subscribe to it. The situation seems perfectly 'natural.' The moral and charitable leadership of the monarch also bind them and incorporate them into the prevailing structure of power. But with the Arab Spring, gossiping about the astronomical wealth of major national power brokers may scandalize the public, and the difficulty of reforming the system with these groups still ensconced in privilege may awaken the silent majority of Moroccans to the hidden truth of their exploitation and put their loyalty to the current political system at stake.

It is interesting that there are some anti-hegemonic jinns who overtly challenge Islamic morality, political authority and western commoditisation, yet even these jinns are basically reproductive, hyperbolic power seekers who drive their mediums to subaltern loyalty and obedience to their commands. They are generally imaginary 'ghosts' of the past, collective local archetypes introjected from incessant daily exposure to hegemonic agents of the Makhzen[5] who left an indelible scar in popular imagination through their misuse of power and constant menace to subaltern populations.

Generally, the survival of jinn eviction and trance dance among the subalterns signifies that social emancipation has not occurred yet and cultural resistance can be seen as a displaced and imaginary activity in which the oppressed exorcise the danger of the imaginary without either daring to face or being mindful of the danger of the real oppressor. Any fear-inspiring coercive menace coming from social realities or unidentified powers may be personified and represented to the imagination under the in-visible form of jinn or evil. They are symbolized with a name, shape and social conduct. Jews, for instance, whom Arabs cannot defeat in reality, are culturally represented as unbeatable spirits. There is a clear consensus among curers and patients alike about Jewish jinn's surpassing powers. They are thought to be the most harmful spirits. Just like their human counterparts, they are believed to be mendacious, may torture the body they visit and may delude the healer during their eviction. In brief, the cultural representation of terror in popular imagination in the form of spirits symbolizes that subaltern cultural resistance through evictions and trance dances remains a cultural practice which can easily be incorporated back into the system, a symbolic space for subalterns to exert some power. Still possession shows aspects of resistance and self-hood apart from prevailing power. So far it has legitimated social hierarchies and asymmetrical relations of power by revitalizing them in rituals. But containment is not defeat. The seeds of rebellion and anti-hegemonic attitudes still lurk beneath the mystic avatars. They are we insist always available for new cultural attachments under new social, political and economic conditions. The resistance and self-hood remain as resources for alternative kinds of expression under new forms and within new conjunctures. As an example, Nas al-Ghiwan (Singing People), a famous musical band who boomed in the seventies and beyond, achieved a tremendous success because their tunes identified with maraboutic melodies of hadra and Sufi litanies. Despite their rejection of moral dishonesty and corruption in Moroccan society and that they ushered seemingly progressive ideas on the scene, Nas al-Ghiwan, influenced by the cultural schemata of their age, called for saints, extolled their qualities and immersed in a trance dance (l-hal) that attracted millions of Moroccans towards such type of music. It was a cultural resistance in which the voice of protest was camouflaged by an escapist attitude gone with the winds of spirits and trance dances. Now, it is rap music that leads the challenge and dissolves fear by seeking confrontation and singing about the minutiae of daily living and the nitty-gritty of how subalterns deal with structural oppression in multiple ways. Rap music is daring and cleaves to a degree the barricades of power, which puts the state on the defensive leading to the persecution of some rebel rappers.

Our basic point is that an awareness of the cultural switch gear during these unsettled times for Moroccan society must grasp the continuing importance of maraboutism, popular culture and subaltern identities in order to have a chance of channeling their cultural orientations towards societal projects that inspire real and not simply symbolic change. Instead of innovating musical festivals like Mawazine to entertain the masses, we need to materially empower popular cultural objects with systems of production and distribution to enable subalterns to have a source of income thus giving new meanings to cultural products. If marabouts were famous for alms-giving to the poor and represented umbrellas of protection to the poor in the past, cultural schemata of this sort should now be secularized and transferred to civic society, solidarity organizations and state welfare institutions but with new cultural meanings. Baraka and mystic powers should be channeled into personal initiative and self dependence. Instead of receiving occasional alms, people should be given opportunities to raise their own capital and start their own trade or business. Cultural meanings should be formulated in terms of action as well as symbols, representations. We think of the metaphor of the 'waterman' drawn from Maarouf`s field notes. The waterman is not a boatman but someone who can fill the empty saucepan of the poor with food. The metaphor of the waterman (mul ma) comes from the story of a prostitute who sells sex in her house. Early in the morning, she fills the saucepan with water and puts it on fire. When her children ask her why she is boiling water, she says that this is a favorable augury that may bring a waterman (sex client) to the house to fill in the sauce pan with meat and vegetables. New societal institutions must be the new material watermen filling the symbolic vessels still held forth not with alms but with self-enabling possibilities.

Islamist Cultural Forms

Islamism finds its social bed with significant sources of recruits in marginalized and economically deprived social settings although the direct link between poverty and Islamism is always discredited (Chekroun, 2005; Lamchichi, 1994; Pargeter, 2009). Islamism grows in areas that have been marginalized over generations, resulting in huge disparities in development with other parts of the country. The case of the Rif in Morocco cursed by the former King is a good case in point. He subdued its earliest uprising in 1958 and 1959. Tangier and Tetouan were punished in 1980's after food riots and Hassan II called them savages. Al-Youssufiya, a poor stop-off for rural migrant workers, was also a cradle of Islamism. It was the social bedrock for Ttakfir wa l-Hijra (Excommunication and Exodus) led by Youssef Fikri (see Dialmy, 2005), or according to Pargeter, a key centre for the Assirate al-Moustaqim (Straight Path) also said to be founded by Yousef Fikri, Justice and Spirituality and Renewal and Reform. One of the Casablanca bombers in May 2003, Youssef Addad, and Abdel Fettah Raydi, who blew himself in an Internet Café in Casablanca 2007, were also from al-Youssufiya.

Casablanca, the Economic Capital city, has been a melting pot of radical ideas with cramped rural migrants on its margins providing a fertile ground for radical Islam which seems to provide certainty and promise. Most recruits are sons of migrant peasants with Islamism flourishing in al-ahya' shsha'biya (popular neighborhoods) either in old medina-s or in the outskirts of the city in the form of shantytowns.[6] Shantytowns revive the tribal structures and old values in new social relations which offer many possibilities for furthering the Islamist desire to uphold conservative Islamic morality against foreign cultural invasion and westernization of the elites whose rich areas, ways of life and value systems are far secluded from the masses. They are becoming the new lands of dissidence (ssiba) to the government.

In point of fact, economic deprivation alone does not explain radicalization. There are many roots for cultural radicalism which is anyway multifaceted. The cultural heritage of political resistance, poverty, marginalization, anomie, social conservatism, flagrant monopoly of polity and economy by prominent families, mass education and mass urbanization, rural migration, capitalism, globalization, and international grievances all combine in a potent mix to produce cultural extremism. People at the bottom of social space may pick up on any relevant set of symbols to deal with their social problems. Islamism answers to the contradictions faced by social conservatism as it collides with modernization in the expanding city. While the regime establishes modern institutions, creates modern concepts and laws to promote modernity and secularism, it is often unable to create the social forces and mental structures that sustain them. In Tunisia, for instance, the state tried without success to combine Islam with secular and modern reason through promoting a French cultural identity, and in a typical response shaykh Rachid al-Ghannouchi, the leader of MTI (Mouvement pour la Tendance Islamique), declared: "we felt strangers in our country." Secularism was an alien guest to a cultural conservative environment that retreated further to Islam in its most simplistic ideologies. The social malaise was manifested in people's preoccupation with morality and social mores (See Moore, 1988, p. 176-190; Pargeter, 2009).

The conservative propensity is also evident in public moderate Islamist discourse also predominant on the Moroccan cultural scene. The questions that the Development and Justice Party [PJD] raised in parliament were usually moral in nature. Moroccan newspapers observed in 2008 that the PJD mobilized 4,000 protestors against what was rumored to be a gay wedding in l-Qsar l-Kebir. Justice and Spirituality (JS), AbdessalamYassine's followers, set up informal morality tribunals at universities in the 1990's[7] to punish inappropriate student conduct. They also divided the sexes on some beach camps such as Bou Naim near Casablanca and l-Harshan near El Jadida; females scarfed and attired swim in seclusion, a form of leisure that was known as halal entertainment, and a holiday experience that was accompanied with unmixed gender cultural and sports events that attracted more than 4000 summer vacationists at the time and could have panned out, had it not been prohibited by the Ministry of Interior headed by the powerful minister Idriss l-Basri. Shshabiba al-Islamiya (Islamic Youth), in its early campaigns, struggled for a moral community promoting bans on alcohol and prostitution, and requiring the institutionalization of Shari'a law. This reformist Islam typically attracts the rural boy who comes from a rural conservative social background. For this usually uprooted itinerant population, the local marabout is of limited use; he can cure minor sicknesses or mediate some personal wish. But collective purist Islam seems to provide the best hope for its adherents to improve their material conditions and bring the hope of emancipation. Those who move to the city to study or work may be fascinated by this traditional reformist discourse and may in turn act as propagandists in the shanty towns.

In the conventional sense of the word and in the past, derbs (neighborhoods) were castles inaccessible to strangers. They signified imagined communities founded on spatial closeness that entailed, assumed and produced social and emotional closeness. It is still the driving force that cements shantytowns and popular neighborhoods together and stands as some kind of resource against the hardships subalterns daily endure. Within the moral spirit and solidarity of the derb, there emerge 'prophets' of what-to-be and what -to-do, i.e., informal sometimes violent justicers who attempt to combat delinquency and moral depravity. Islamist ideologies may inform such action helping to organize youths into intolerant morality defenders but also directing abhorrence towards those at the top of society, who keep the riches for themselves. It has to be emphasized that the Islamic impetus is only one element in the complex and steamy cultural atmosphere of the shanty town. The tumult and emotional effervescence that blaze inside are the result of the collective congestion of hate, social despair and state of paralysis in which subalterns live. As well as they can be attracted by Islamist ideologies, youths can expend their energies when they come across a little cash on cigarettes, shisha, hashish, alcohol, prostitution and other sorts of toxicomania. Adults in their turn can resort to the eviction of frustrations in ritual dances, and ceremonial acts of magical emancipation. Such ritual licensed outlets may enable them to release themselves from the burden of guilt inflicting blame on social stereotypes of the other.

It is of great interest that via the internet revolution, there appear new derbs online creating new cultural spaces enabling radical Islamist ideas to migrate trans-nationally and to help form up groups of militants from different nationalities; ideas may circulate via CDs, satellite channels, websites and e-mails beyond the state's control. From perusing media accounts and state reports it can be ascertained that the organizational structure of the new Islamists' groups seems to be based not on a conventional organization of cells and agents. It is now more a force field of potential rather than tangible structure. When tangible organizations are needed, they are imported or constructed or suddenly appear. Those who would control the jihadist operations do not need to organize themselves in a conventional manner to maintain their struggle. They do not need furtive gatherings and secret armies. Instead, there are people who appear and disappear, actions that mutate. No leader is required to coordinate all the efforts. One may capture rebels but not necessarily the rebellion, not if the ideals are still rampant, the grievances experienced, and the duty of jihad calling. This Jihad may be blessed by al-Qaeda leaders but the latter has no command or control centre. This is the latest generation of the Islamist commando that may be termed leaderless jihad (cf. Sageman, 2008).

In this liquid social context, Ben Laden reminds us of a traditional female dancer nicknamed Kharbousha who lived in the second half of the nineteenth century in Safi region in Morocco and was persecuted together with her mutinous tribe Ouled Zid by an oppressive Qaid named Isa Ben Omar who attacked her tribe and killed her family. In revenge she belittled his power in her songs of Hate and awakened the tribes to his oppressive rule to the extent that the fame of her songs grew outside her region and tribesmen sung them in the fields and entertainment gatherings in different parts of Morocco. The qaid captured her, tortured her and killed her but all of it in vain. He could not kill the voice of revolution; the songs migrated among Moroccans who rehearsed them to fight oppression; the spirit of Kharbousha survived in popular music with melodies from Nas al-Ghiwan and Jilala who composed songs of political resistance in the eighties. Similarly, Ben Laden and al-Qaeda may be finished but USA is not winning the war. As a spirit, a set of beliefs and as a form of political resistance, al-Qaeda will never come to an end so long as Muslims feel they suffer unanswered grievances and remain without sufficient tools of self-defense. This global force field is opportunist in that it may avail itself of conventional organizations, cells, spies, ideologues, funders, charity people, robbers, smugglers, operational experts and bomb makers but none of these are necessarily organic members of al-Qaeda. They often seem to appear without warning or preparation.

According to Bell (2002), the great advantage of the force field is that it does not rely on skills and competence. This may come as a bonus to the movement. What is important is the conviction of the recruits. The faithful do not learn their terror trade. They rely on their faith and God's help. The Qur'an substitutes for marksmanship. No one wants to pursue the vocation of a terrorist; they just need to win once. So, there are no professional terrorists who want to improve their skills, but faithful jihadists who rebel against the status-quo and, unlike their parents who have chosen magical emancipation and escapist solutions, they decide, as they see it, to bear arms to change history. Jihad becomes a duty especially in Arab lands occupied by the secular West under the guidance of the 'Great Satan Israel and its ally USA'. Many young Islamists are caught in the dream.

Traditional maraboutic practices of self-flagellation, cultural rituals, violent exorcisms and trance dances performed by subalterns seem to be forsaken by the new generation of radical Islamists who are saturated by the spirit of Jihad. Emancipation for the new generation comes through the myth of martyrdom. They 'choose' to hold guns to attain their targets. These rebellious youths do not blame it on spirits and jinn but on rulers and their Western guardians. They perceive the alliance of the West with local tyrants as a camouflage to eliminate internal opposition in the name of the "war on terror." They refuse to wear western binoculars to see their own world because the West for them is an expansionist, imperialist capitalistic exploitative power. This does not mean that there has been a cataclysmic switch from cultural escapism to radicalism. In between there has been an organized post maraboutic civic movement against traditional non-effective cultural modes of resistance; a modern, philanthropic, welfarist model based on traditional reservoirs, tolerant and forgiving, but does not mean cowardish and renouncing. This can be found in modern civic activism, conventional Islamist organizations, and wealthy altruists. The new generation is not all constitutive of mujahids; there are silent bystanders or risk avoiders who withdraw to watch the political game from afar for fear of being in trouble. There are those who are recruited in the present political game for personal material profit but there exists a minority of awakened activists and players who fight for a peaceful democratic change though their modus oprandi of realizing this change remains a grey zone.

The Moroccan case is of course a special one because it has a sacred monarchy thought to be legitimated by a divine law (see Arroub, 2004; Hammoudi, 1997, 1999; Tozy, 1999). The king is the commander of the faithful, unlike the presidential state—the case of Algeria and Egypt—in which the political contest may go to the presidential office. Hassan II was clear on this when he said: "I will never accept to be put inside the equation" (Zartman, 1986, p. 64). In Morocco, the political players' contest is contained within parliamentary boundaries at least for the moment which may help to explain the relative social stability and subscription of subordinate social groups in Morocco to the cultural and political meanings of the prevailing structures of power. Our general argument here is that Islamism is not born a monster which can only be exorcised through a civil war. It is a culture that gives birth to radical thought under particular social, economic, and political circumstances and constraints. Not all groups are violent; many are participating in the democratization process of their countries. PJD, for instance, abides by the rules of the political game and legitimates the monarchic rule.[8] Even the now seemingly violent Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), first participated in Algerian politics till its expulsion from the democratic game in 1992 after it won the first round of elections in 1991 when it resorted to arms. Justice and Spirituality (JS), a Moroccan radical group semi-banned by the state, does not accept the rules of the political game but now its discourse is aligned with constitutional reforms (see Arroub, 2009; Darif, 1995; Tozy, 1999). For western politics, the Islamist field is really a "grey zone" (see Brown et al., 2006); westerners feel threatened by Islamist bullies; they think if the monster wins, he may implement policies detrimental to the US and European interests though in the long run local Islamists seem also to participate in their country's stability.

What is crucial for all parties to realize is that reform, political transition and some kind of arrival into Moroccan modernity will only be achieved when borne in and by matching social practices and changed quotidian cultural forms, especially religious ones. The dual problem Arab revolutions face is not only unseating authoritarian regimes but also the development of adaptive popular cultural forms which are the only long term guarantees of political change.[9] At this stage, they face a looming threat. It lies in a silent majority who may jeopardize the revolution by betraying it in the Gramscian sense of the word.

Islam must adapt itself to the political revolution and modernize itself without resort to extremism. Taking our cue from Arkoun (1992 and 1994), we argue that there is an urgent need to approach mainstream Islamic culture and tradition from a critical interdisciplinary perspective. The main objective is to dismantle the unthought' and/or the 'unthinkable' in classical and modern Islamic thought. The 'rethinking of tradition' or even 'rethinking of the Quran' needs to be expanded into a new 'rethinking of Islam in general.[10] By promoting the analysis of the historical, cultural, social, psychological and linguistic contexts, it must be possible to emancipate the 'unthought' and/or the 'unthinkable'—such as the rule of law and civil society— to initiate "a radical re-construction of mind and society in the contemporary Muslim world" (Arkoun, 1994, p. 1). Issues such as the nature of revelation and the holy book, secularism, and individualism are all 'unthought' and 'unthinkable' due to the dominant position of orthodoxy in the history of Islamic culture. The building block in this project is the critique of Islamic reason (Arkoun 1992, p. 17), the withdrawal from classical ijtihad that is restricted by the epistemological constraints established by jurists in the 8th to 9th centuries, and the effectuation of a modern critical analysis of the structure of Islamic reason.

New Media-Inspired Cultural Forms

The Moroccan national media which might have played a developmental role promoting national language and culture and carrying out tasks of social and educational development instead devote their efforts to entertainment. Moroccan Radio and Television (RTM) and 2M Maroc frequently schedule football games, music shows, and Turkish and Mexican films dubbed in dialect with very few social and political programs. Print journalism retains only a small presence in Morocco. Circulation does not exceed 650,000 copies per day (al-Yahyaoui as cited in al-Hilali, 2012). The national market of print journalism is made up mainly of political parties' press and a few independent journals; all remain more or less unprofitable. Illiteracy rates are high. Lots of schooled youths spend their free time in internet shops and Cafés where they access chat rooms and websites to download music and films, the price of which exceeds the price of a newspaper but do not read written press. Many professionals such as engineers, doctors, educators, businessmen do not have the cultural habit of reading daily newspapers. Mokhtar al-Harras, a Moroccan sociologist, explained in a press interview that the results of his fieldwork research on print journalism demonstrate that only 9% of youths aged between 15-29 read newspapers, 37% occasionally and 47% not at all—needless to mention that a considerable rate of those who read newspapers are interested in sensational news stories and cross-word puzzles.[11] 60% watch foreign satellite channels and the rest watch national ones (cit. in Liman, n.d.). The rich are Francophone; yet most newspapers are in Arabic. Newspapers in Arabic constitute about 75% of the market but advertizing goes to newspapers in French. Newspapers are distributed on a small scale concentrated in the urban centers of Casablanca and Rabat which account for 50% of sales. The lack of rapid means of transport makes many regions in Morocco difficult for paper distribution.

As liquid modernity is producing liquid information, the written press in Morocco is ceding terrain to digital communication. Facebook and Twitter show thousands of messages and videos every minute and citizens exchange information, comments, opinions and advice. Many young people chat on the internet for various reasons. They exchange opinions or information, pursue fun or friendship, sexual relations, explore possibilities for immigration or for intercultural marriages. After the Facebook mediated revolution in Tunisia and Egypt, Moroccan Facebookers launched a campaign for political reform which led to collective protests at street level nation-wide on 20 February 2011. The 20th February movement insists on a bottom-up reform based on the sovereignty of the people with a constitutional monarch and a government which outlaws corruption and promotes economic and educational investment as well as providing public health care and social security. Ever since that date, each Sunday young protestors in different Moroccan cities and villages take part in street demonstrations to call for political and economic reform. Though the King delivered a speech on 9 March launching a constitutional reform, the movement saw in the King's initiative only a symbolic gesture that did not meet their expectations.[12] The Movement demands radical political reform in which the king reigns but does not rule and requires the exclusion from politics of the old guards of the monarchy. Though the movement was born in virtual space its members and sympathizers also gained experience in street protests, especially with the earliest participation of Justice and Spirituality (JS) and some civil society organizations. The 20th February movement protests persist in the face of detentions, suppressions and Makhzen penetrations of militants' lines. As an activist respondent puts it: "The Makhzen bets on winning the game like a team who enters the competition not to display its style of football but to block the other team (y-khaser lla'b)". In fact, the 20th February movement is stumbling since its emergence because it hosts incongruous trends and groups which include: Islamists, secularists, opportunists and a variety of different interest groups. In addition, the bloody and gridlocked events in Syria, the foggy political atmosphere in Egypt with the possibility of new Islamist authoritarianism and the violent confrontations in South Libya and Tunisia to say nothing of the of the Makhzen's continuing iron grip in Morocco [cleansing public places of wandering vendors and demolishing illegal suburban housing]; all emphasize the potential human wastage and uncertain future of revolutions. The 20th February movement, itself, is in need of a cultural switch gear understanding and strategy as called for in this article.

It is obvious from the movements' messages, slogans[13] and public speeches that there is no intent to overthrow the political system but to create a paradigm shift in the relationship between the monarch and his subjects. The protestors want to move from being King's subjects to modern citizens. They want a Monarch to referee and a state leader to be elected by the population and be accountable to its representative institutions. Not all those who take to Moroccan streets are aware of these political demands; poor working classes, and the rank and file of subalterns are mainly focused on their economic rights. Also, organizations of the unemployed graduates, for instance, are active participants in Sunday protests; sometimes they take to the streets on Saturday to highlight their own specific sectional employment demands within the 20th February movement as a whole.

Though the movement is so far contained and put on the defensive by the policy of the Makhzen, the containment may not stand against continuing waves of protest and raised expectations set against a deteriorating economic backdrop. Revolution can still be in the wings if the multitude of the unemployed cannot find jobs, if price inflation persists and public hospitals cannot offer decent, free health care. While observing the 20th February movement during its protests at the local level, we discerned an awakening of young educated subalterns to political resistance against corruption, clientislim, patronage and authoritarianism. Nevertheless, the movement has been facing many difficulties in its political scramble with the monarchy. Even if Moroccan militant Facebookers have reached some distant tribes and villages, they still have a long road to go to take their message to the far distant neglected rural populations. The Internet form can alienate the movement from that face-to-face contact within which subalterns are immersed. Besides, state-mandated media do not report the 20th February activities. Our sense is that the masses know exactly what they suffer from but they lack the political consciousness to grasp the relationship between macro-structures and micro-situations. Therefore, the task of the 20th February movement must be to educate subaltern masses on how to address their economic problems awakening them from fatalism to political struggle though some of the forms of that may be continuous with traditional cultural ones. This project of awakening may last for years if not for generations depending on how the movement grapples with the suppression of the Makhzen. The latter so far succeeds in its containment policy but revolutions in communication erode state control of media institutions everywhere and the Makhzen's stratagems are more than usually obsolete with few new digital tactics of communication and social control.

Meanwhile the 20th February movement is visibly developing its own deep culture of resistance sustained with slogans, ritual behavior, uniform and chants. Rap music proliferates in the movement's activities both on the internet and in the streets. This type of music is becoming the angry voice of youth protesters. One of the leaders of this musical movement, Mouad Belghawat nicknamed "Resenter" (al-Haqid), has been imprisoned twice and is now back in jail for his stinging musical attacks on the monarchy and the apparatus of the Makhzen.[14]

To further illustrate this rising culture of resistance, we offer some examples of challenging subaltern discourses appearing through the mediation of the 20th February movement. They express economic dilemmas confronted increasingly for themselves not through mysticism, though strong traces of the latter remain. They do tear off the mask of fear and there is some intrepidity here in speaking the subaltern mind more directly. Below are three young subalterns breaking the ice and speaking in front of camera for the 20th February movement, expressing their anger at being duped by local authorities. Here is the summary of their video shared on the movement's Facebook page on 28 December 2011 at 22:44:[15]

First Speaker: I first thank the king and long live the king and long live the Alawite family. We love the Alawite family to death but we live in alarming conditions…On the day of elections, the authorities asked us to work with them; they gave us election dress, brochures, and we knocked on doors to sensibilize citizens to go to vote. The mqaddem (caid's agent) was with us and we executed their orders to the letter but they exploited our poverty. I who is talking to you was prisoner for 16 years, six times I was unfairly taken to jail, but we say that we leave everything to God, and we are now without work and this is the café where we sit and people know that Abdelkader sits here. And the Makhzen always comes to arrest me from here. And when we wanted to be reasonable and worked with them, now this is a month and a half and they have not yet paid us. Why should not they pay us? What is 400 dh? A whole government and a parliament overwhelmed with parliamentarians and 400 dh of ours they do not give it to us. This morning they came and switched off the water mains. Am I not a citizen? Do I not have the right to drink water? If they had given me 400 dh, I would still have water. We have no work. My father is retired and earns a pension of 500 dh per three months, what is he going to do with it? Eat with it, pay bills or buy medicine or spend it on his unemployed children?

Second Speaker: [….] We did the national duty of informing the citizen in order to make elections successful but they exploited us because we sit in the café and have nothing to do.

Third Speaker: [….] Give me work and see if I will carry on asleep. I am still young. Shall I ask for charity but it is beneath my dignity. The 'dixilun' (industrial zone) is all closed; they can open four or six factories and call people to work. You do not have anything and another one whose father god knows who he is, very rich, drives an expensive car passing through and you…Well, may Allah give him more; they just give us where to work, we do not envy anyone, if you get sick, Allah is the curer; you stay home, you cannot go to a doctor; you need 100 dh, where can you find it? You keep home-bound till God sends his cure to you and you stand up. Do they want us to remain like this? We go to the café in the morning and at lunch we go back home because the old parents provide the food. Then back to the street again. We do not know who is responsible but God will take revenge from them for what they are doing to us. Long live the king and long live the Alawite family.

First Speaker adds: "You know, I went for three suicide attempts in prison. Once I screwed a barbecue stick down my throat, another time I jumped out of the third floor in 2001 in prison Zlleilig and broke my chest ribs. I spent my life afflicted by prison sentences and I lost to know what to do, maybe a suicide attempt in a place no one can foresee , I am taking medicine and I have my papers of insanity, and nobody cares about me. And this is even my voting card; we vote like them and long live the king! Long live the king….finished!

Our second example is from a video[16] posted by the 20th February movement on its page on 04/12/2011 showing an old woman in her eighties who joins the protests in the streets, watching the crowd from her window; she yells in an angry voice that embodies the rancor subalterns feel. Formed in traditional cultural and linguistic ways, her speech is still quite far from and does not echo the political jargon of the elite. In the middle of the protests, she raises her lamenting voice: "You are thieves and enemies of Allah! You killed us of hunger! A loaf of bread is 30 ryals (1,50 dh), oil 300 ryals (15dh), you Nazarenes, apostates! Fuel it up upon them! God damn their fathers! Tell them: 'God Damn Your Fathers!'

The resentment subalterns vent on the state is epitomized in the unspecified pronoun 'them'. Though challenging, subaltern discourse is still caught within authoritarian assumptions and conventions. All actors formulate the political problem in immediate economic terms and insist on their allegiance to the King. The boys do not evince any volition to act through their own agency. They rather express themselves through idioms of luck and God's intervention, and look at themselves as victims in need of a saviour. The old woman does not protest but rather wails and insults: the commonest weapons of subalterns. The explicit and short term economic aspect of subaltern demands, whilst capable of further development under the right conditions of culture and organization may also give the state a strong short-term foothold to purchase subaltern loyalties within a traditional cultural gift-exchange model built on rewarding loyal and discrete allies and collaborators with state-subsidized benefits and services. By means of exercising a cultural schema of charity,[17] perhaps the Makhzen can still mollify subaltern anger and win their support by means of alms distribution.

Morocco at the Crossroads

Dominant groups sweat over clumsily the cultural switch gear trying to ensure the continuing popular acceptance of authoritarian rule and the successful exercise of power through structures of charity and fear. Meanwhile many of our respondents say that they are not ready to sacrifice death or injuries to bring about political change. When interviewed, most say that they do not queue up for bread or chicken like the Egyptians. A recurrent statement we hear is that "in Morocco, thanks to God, there is prosperity (hamdu Allah al-khair mujud)." Even the unemployed can tinker and get a day's income of 100dh to get by on. For them the example of Lybia, Syria and Yemen is rather frightening. It deters people from being recruited into a violent protest against the regime. There is also always hope for a charitable gesture from the monarchy to make economic compensation and relieve subaltern poverty.

Up to now, there are no clear ethnographic signs that display whether Moroccans are likely to risk going for a real, perhaps bloody, confrontation with the regime, especially given that the monarchy is now `inside the equation` and insists on leading political change. But Moroccan history— the Kumira (loaf of bread) Revolution in the 1980's[18] is a good case in point— bears witness that riots on the rebound of an economic crisis may get out of control and may even under special circumstances turn into popular revolutions. We are in special circumstances now and we should be alert to the cultural switch gear and micro gear that may be critical to the outcome of unfolding events.

The Makhzanian strategy of containment and policy of daily patching and assuagement may win time but with potential disastrous consequences for them in the long run, especially if the process of awakening—no matter how it is communicated—reaches the remote regions of the North and East in Morocco. Political regimes founded on security forces alone are bound to be overthrown. Those founded on ideologies internalized by the masses may last till overthrown by counter-hegemonic ideologies. The uncertain building of the latter may now be in progress. The demands are clear: real freedom of speech; meaningful participation in institutional process and decision making; real moves towards social protection and social security; respect for the rule of law. But without the building bricks of a culturally sensitive mode of politics and mobilization foregrounding the importance of culture, the counter-hegomonic currents may fail leaving Morocco in stagnation, at peril simply of painfully and tragically reproducing what has so far been struggled against. To maintain and strengthen currents of change, discourses on citizenship, democracy and human rights must be formed in, and linked to, sensuous cultural practices and local cultural meaning—making so that citizenship becomes lucid in the subaltern mind as a familiar thing, as a recognizable cultural citizenship and which encourages bottom-up cultural forms and implicates subalterns in self-critique and self-development of their own cultural models. Understanding cultural switch gear, and developing switches and switchmen for a micro cultural switch gear is an essential ingredient for the counter-hegemonic struggle in Morocco today.

References

al-Achraf, Hasan. (2012, August 11). al-Ghali: I'tidar Benkirane "ghair dusturi" wa yu'abbir 'ani al-wala' wa l-khudu' [al-Ghali: The apology of Benkirane is "unconstitutional" and expresses allegiance and submission]. Hespress. Retrieved August 13, 2012, from http://hespress.com/politique/60301.html.

Arkoun, Mohammed. (1992). De l'ijtihâd à la critique de la raison islamique. In Lectures du Coran (Mina al-ijtihâd ilâ Naqd al-'aQl al-Islâmî), Arabic translation of the French 2nd revised edition (Tunis, Alif, 1991) by Hashim Sâlih, 2nd edition, London: Dar al Saqi.

------------------. (1994), Rethinking Islam: Common questions, uncommon answers (R. D. Lee Ed. & Trans.). Oxford: Westview Press.

Arroub, Hind. (2004). Al-Makhzen fi a-ththaqafa a-ssiyasiya al-maghribiya [The Makhzen in Moroccan political culture]. Rabat: Dafatir Wijhat Nadhar.

---------------- (2009). Al-malakiya al-muqaddasa wa wahm ttaghyyir [The sacred monarchy and the illusion of change]. Wijhat Ndhar, 42, 6-13.

Benomar, Jamal. (1988). The monarchy, the Islamist movement and religious discourse in Morocco. Third World Quarterly, 10 (2): 539–55.

Bell, Bowyer J. (2002). The organization of Islamic terror: The global jihad. Journal of management inquiry, 11 (3): 261-266.

Brown, Nathan, Amr Hamzawy, and Marina Ottaway. (March 2006). Islamist movements and the democratic process in the Arab World: Exploring gray zones. Carnegie Papers, 67, 1-19.

Chekroun Mohammed. (2005). Socio-economic changes, collective insecurity and new forms of religious expression. Social Compass, 52(1), 13–29.

Crapanzano, Vincent. (1973). The Hamadsha: A study in Moroccan ethnopsychiatry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Darif, Mohammed. (1995). Jama'at al- 'Adl wa l-Ihsan : qira'a fi al-masarat [Justice and Spirituality: A reading in their routes]. Casablanca: al-Majalla al-Maghribiya li 'Ilm al-Ijtima' Ssiyasi.

Dialmy, Abdessamad. (2005). Le terrorisme islamiste au Maroc. Social Compass, 52(1), 67-82.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1990. Selections from the prison notebooks, (Quintin Hoare & Geoffrey Nowell Smith Eds. & Trans.). New York: International Publishers.

Halim, Abdeljalil. (2000). Structures agraires et changement social au Maroc. Fès: Faculté des Lettres.

Hammoudi, Abdellah. (1997). Master and disciple: The cultural foundations of Moroccan authoritarianism. Chicago: U of Chicago P.

------------------. (1999). The reinvention of dar al-mulk: The Moroccan political system and its legitimation. In R. Bourqia & G. S. Miller (Eds.), In the shadow of the sultan: Culture, power, and politics in Morocco (pp. 129-175). Cambridge: Harvard Center for Middle Eastern Studies.

Khosrokhavar, Farhad. (2005). Suicide bomber: Allah's new martyrs (David Macey Trans.). London: Pluto Press.

Kolakowski, Leszek. (1971). Hope and hopelessness. Survey, 17 (3): 37-52.

Lamchichi, Abderrahim. (1994). Etat, légitimité religieuse et contestation islamiste au Maroc. Confluences Méditerranée, 12, 77-90.

Laroui, Abdallah. (2001). Al 'alaqa bayna al-zzawaya wa l-Makhzen fi al-qarn 19 [The relationship of zawiyas and the Makhzen in the 19th cent] (Nawal Al Mutazaki, Trans.) Amal, 22–23: 7–26.

Liman taktub al-ssahafah al-maghribiyah al-maktubah?: 9% faqat mina al-shshabab yaqra'unaha [For whom does print journalism write?: Only 9% of youths read it] (n.d.). Hiba-press. Retrieved November 2, 2012, from http://www.hiba-press.com/...

Maarouf, Mohammed. (2007). Jinn eviction as a discourse of power: A multidisciplinary approach to Moroccan magical beliefs and practices. Leiden: Brill.

----------------------------. (2010). Saints and social justice in Morocco: An ethnographic case of the mythic court of Sidi Chamharouch. Arabica, 57 (5–6): 589–670.

----------------------------. (2012a). Jinn possession and cultural resistance in Morocco. Manuscript in preparation. El Jadida: Chouaib Doukkali University.

----------------------------. (2012b). The cultural foundations of the Islamist practice of charity in Morocco. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, 24 (1), 29-66.

----------------------------. (in press). Suicide Bombing: The cultural foundations of Allah's New Version of martyrdom. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture.

Moore, Clement Henry. (1988). Tunisia and Bourguibisme: Twenty years of crisis. Third World quarterly, 10, 176-190.

Pargeter, Alison. (2009). Localism and radicalization in North Africa: Local factors and the development of political Islam in Morocco, Tunisia and Libya. International Affairs, 85(5), 1031–1044.

Pascon, Paul. (1983). Le Haouz de Marrakech. Vol. 2. Rabat: Centre Universitaire de la Recherche Scientifique.

-----------------. (1984). La maison d'Iligh. Rabat: Société Marocaine des Editeurs Réunis.

Pennell, C. Richard. (2003). Morocco: From Empire to independence. Oxford: Oneworld.

Ramadan, Tariq. (n.d.). Trying to build a great divide. Interview by Nicholas Le Quesne. Retrieved March 18, 2010, from http://www.time.com/time/innovators/…/profile_ramadan. htm

Rouhi, Ismail. (2012, October 27). al-Masae takhtariqu shabakat tajnid al-Magharibah li l-qital fi Suriya [al-Masae intrudes into a network for the recruitment of Moroccans to battle in Syria]. al-Masae. Retrieved October 29, 2012, from http://www.almassae.press.ma/node/55580.

Sageman, Marc. (2008). Leaderless jihad. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Shahin, Emad Eldin. (1998). Political ascent: Contemporary Islamic movements in North Africa. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Tozy, Mohamed. (1999). Al-malakiya wa l-islam ssiyasi fi al-Maghreb [Monarchy and political Islam in Morocco] (M. Hatimi & K. Chakraoui, Trans.). Casablanca: Le Fennec.

Walstrom, Mary. K. (2004a). Ethics and engagement in communication scholarship: Analyzing public, online support groups as researcher/participant-experiencer. In E. A. Buchanan (Ed.), Virtual research ethics: Issues and controversies (pp. 174-202). Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

————. (2004b). 'Seeing and sensing' online interaction: An interpretive interactionist approach to USENET support group research. In M. D. Johns, S.-L. S. Chen & G. J. Hall (Eds.), Online social research: Methods, issues, & ethics (pp. 81-97). New York: Peter Lang.

Weber, Max. (1946). Science as a vocation. In H.H. Gerth & C. Wright Mills (Eds.), From Max Weber: Essays in sociology (pp. 129-156). New York: Oxford University Press.

Willis, Paul, and Mohammed Maarouf. (2010). The Islamic spirit of capitalism: Moroccan Islam and its transferable cultural schemas and values. Journal of religion and popular culture, 22 (3). http://www.usask.ca/relst/jrpc/art22(3)-islamic-spirit.html.

Zartman, William. (1986). Opposition as support of the state. In A. Dawisha & W. Zartman (Eds.), Beyond coercion: The durability of the Arab state (61-87). London: Croom Helm.

Photo Gallery

The Association of the unemployed participating in the 20th February movement's demonstrations with the slogan of "look at graduate degrees in plastic bags!"

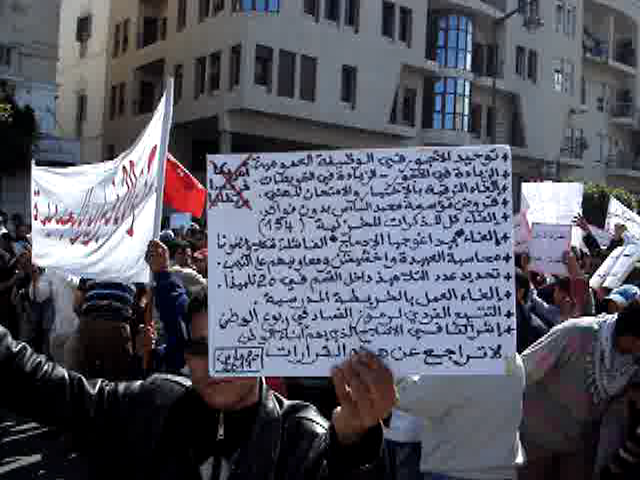

The 20th February Demonstrations in El Jadida showing pictures and raising slogans against corruption

The 20th February movement during a sit-in in El Jadida on a Sunday

The 20th February demonstrators holding signs declaring their condemnation of all forms of terrorism

Notable participation of children, also conning the slogans of the movement and rehearsing them in their games, thus may be drilled in new cultural schemata of resistance.

A demonstration showing a big sign with faces and names of martyrs of the movement. The militant in front holds a sign on which is written: "the voice of Moroccan peoples frightens the corrupted, cowards, is supported by patriots and honest people and joined by heroes" (from the movement website on 24 October 15:30)

During demonstrations, most signs held forth basically express social and economic demands of the movement to attract subaltern support.

A sign insisting on the peaceful nature of the movement's protests.

Young and adult females are active participants in street demonstrations

Justice and Spirituality women are also conspicuous participants in outdoor demonstrations

A female collegian activist leading many of the demonstrations of the 20th February movement in El Jadida.

A male collegian activist leading many of the demonstrations of the 20th February movement in El Jadida

Sometimes groups or participants may not agree on the agenda and skirmish during demonstrations: here the skirmish was between the 20th February members and members of the Association of the Unemployed over which slogans to give priority.