All Things Dracula:

A Bibliography of Editions, Reprints, Adaptations, and Translations of

Dracula

compiled by

J. Gordon Melton

A joint project of the Transylvanian Society of Dracula U.S. and Italian chapters

Note: Chapters whose titles appear in red are forthcoming and will be gradually added in order to complete this project.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Dracula, the Text

Stokerís Notes on Dracula

Appendix I: Christieís Description of the Dracula Manuscript (Auction of April 15, 2002)

Section I. English-Language Publications of Dracula

A. The British (Constable-Rider) Tradition

B. The American (Doubleday-Grosset and Dunlap) Tradition

C. Dracula Editions, 1962-Present

D. Mass Market Paperback Editions

E. Omnibus Editions

F. Annotated Editions.

G. Excerpts Printed in Short Fiction Anthologies

Appendix I: Hutchinsonís Colonial Edition of Dracula, by Robert Eighteen-Bisang.

Appendix II: The 1901 Paperback Edition of Dracula: Introductory Material from the 1994 Reprint, by Raymond T. McNally.

Section II. Dracula's Guest

Section III. Adaptations

A. Dramatic Adaptations of Dracula

B. Cinematic Adaptations of Dracula

C. Audio Adaptations of Dracula

D. Textual Adaptations of Dracula

E. Graphic Art Adaptations of Dracula

F. Study Guides

Section IV. Translations

Chinese

Czech

Danish

Dutch

Estonian

Finnish

Flemish

French

Gaelic

German

Greek

Hebrew

Hungarian

Icelandic

Italian

Japanese

Korean

Lithuanian

Malaysian

Norwegian

Polish

Portuguese

Romanian

Russian

Spanish

Swedish

Thai

Ukrainian

Section V. Contemporary Appearances of Dracula

A. Cinematic Appearances of Dracula Since 1931

B. Dracula in Novels

1. Sequels to Dracula

2. Dracula's Victorian Adventures

3. Dracula as Vlad Ţepeş

4. Contemporary Adventures of Dracula

C. Dracula in Short Fiction

D. Dracula in the Graphic Arts

Introduction: Dracula, the Text

As the twenty-first century begins, it no longer seems necessary to make a case for Dracula, the horror tale composed by Bram Stoker at the end of the Victorian Era in England. It has received ample recognition as one of the truly great horror stories of Western fiction, it is regularly the subject of academic courses ranging for gothic fiction to modern mythology, and a century after its original publication remains in print in a host of editions, adaptations, and translations.

This modest project traces the editions and printings of Dracula in the English language, lists the books and various media (film drama, audio recording, etc.) into which Bram Stoker's account of Dracula has been adapted, tracks the translation of Dracula into the several dozen languages in which it has appeared, and surveys a set of material which has been directly inspired by the text and its vampire star. This list was initially developed from the collection of the author, but would have not been possible without the additional references to the very extensive collections of Robert Eighteen-Bisang, Massimo Introvigne, and Bob and Melinda Hayes (the latter posted on Melinda's extensive website (http://isd.usc.edu/~melindah/Stoker/dracthum.htm). Between them, these four sources contain copies of almost every English-language printing of Dracula, and a great majority of the adaptations and translations.

The several forms in which the text of Dracula exists creates a spectrum of problems for any serious student of gothic literature, and that spectrum of problems increases exponentially as soon as the many adaptations of the text, especially the cinematic ones, are introduced into the discussion. Of course, those same problems have been the stimulus that has allowed Dracula and vampire studies to flourish in the last generation. While not in itself solving any of these problems, it is hoped that this guide to the various forms in which Dracula exists will be a useful map for approaching the problems.

The development of interest in Dracula in the last generation coupled with the knowledge of the many forms in which it exists has also stimulated collectors. Dracula is now a favorite target of collectors, and the compiler hopes that as a secondary goal, this bibliography will become a helpful tool for fellow collectors as they do their own explorations of the many realms into which Dracula has penetrated.

Approaching Dracula

In approaching the ever-changing appearances of Dracula, one might logically begin with the publication of what was surely intended as the book's first edition by Archibald Constable & Co. at some point in May or June of 1897, the exact date of the book's release, if such a date existed, being unknown. Most Dracula scholars place that date in late May or early June. The Constable edition had a mustard yellow cover sans dust jacket with the title in red. For most books, the publication of its first edition is a firm foundation from which to consider later permutations, not so with Dracula. Dracula exists in two important textual formats that pre-date the first edition, namely the set of extensive notes made by Stoker while he went through the lengthy process of writing his novel, and the typescript that was submitted to Constable from which the typesetting was done.

It should be noted that interest in Dracula in the academic community was slight until the early 1970s. The current seeming feeding frenzy around what many considered a horror potboiler began with two historians who made the connection between the name of Stoker's title character and the Medieval Romanian Prince Vlad Dracula. Their search for documents related to Vlad led them to the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia. While there, they made an entirely unexpected discovery, Bram Stoker's notes on Dracula, compiled as he researched and thought through the plot and characters for his novel. These notes had been originally auctioned by Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge in 1913. Over the intervening years, knowledge of their location was lost until the Rosenbach acquired them in 1970. At the time of McNally and Florescu's visit, an entry on the Museum's newly acquired item had not yet been placed in the library catalog.

Following their visit to Philadelphia, McNally and Florescu went on to write the breakthrough study, In Search of Dracula. The idea that Stoker's Count Dracula was based upon the real historical character Prince Vlad caught the imagination of a generation. Not only did the book become a bestseller, but it stimulated three decades of inquiry by a spectrum of scholars into the origins of Dracula. The contemporary interest in vampires throughout the academic world from nineteenth-century gothic literature to Buffy the Vampire Slayer can be traced to the reaction to this single volume and the discovery of the Stoker notes.

Note: in 1997, the Rosenbach Museum organized an exhibit on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the publication of Dracula in which they displayed a selection of their Dracula-related material. As part of the celebration, they also published: Bram Stoker's Dracula: Catalog of the Centennial Exhibition at the Rosenbach Museum & Library. Philadelphia: Rosenbach Museum & Library, 1997. pb. Large format. Cover by Maurice Sendak. Limited to 1,000 copies. This pamphlet contained 12 b&w reproductions of pages from the notes.

Meanwhile, it also happened that quite independently of McNally and Florescu, another young scholar was also working on Dracula, making his start from the many incarnations of the novel in popular culture through the twentieth century. And like In Search of Dracula, Leonard's Wolf's Dreams of Dracula appeared in 1972. Wolf would go on to compile the first set of scholarly notes on the text which appeared in 1975 as The Annotated Dracula. Still unaware of the notes that lay at rest in Philadelphia, Wolf asked most of the right questions of the text although, without Stoker's notes, in many cases his answers would later prove incorrect. McNally and Florescu would bring out their own annotated text in 1979 as The Essential Dracula.

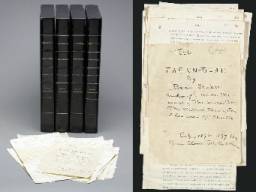

As Dracula scholarship emerged, it also become known that at least one copy of Stoker's final manuscript had survived. In 1984, California bookstore owner and collector John McLaughlin was offered the manuscript by an anonymous seller. He purchased it and then in 2002, placed the manuscript, a typescript of the last draft of the text with handwritten changes, up for auction.

McLaughlin had designated a minimum bid, reportedly one million dollars, but instead of the many bids that he and Christie's Auction House had waited for, none appeared. However, when McLaughlin checked in with Christie's, he was informed that the manuscript had been sold under a clause that allowed the sale of items after the auction. While no one bid at auction, someone had paid $941,000 for it later. Although McLaughlin received a substantial sum, it was far less than he had hoped.

Stoker's typescript of Dracula is notable for bearing the author's original handwritten title for the work, The Un-Dead. It was probably typed by Stoker in London early in 1897 or in 1896 and is the only surviving full-length manuscript of Dracula. It is an important clue as to the process of the development of the eventually published text. While generally unavailable today for anyone to examine, a rather detailed description of the manuscript was included in the booklet printed by Christie's in anticipation of the auction: Bram Stoker's Dracula: The Original Typed Manuscript. Wednesday 17 April 2002. New York: Christie's 2002. 44 pp. pb. It also posted much of the text from that booklet on its Internet site.

The process of publishing the manuscript, was, we now know, accompanied by several important decisions. First, in 1914, after Stoker's death, his widow Florence Stoker claimed that a chapter had been removed from Dracula, presumably to shorten it and bring it into conformity with what the publisher saw as an optimum length for a popular novel. She published that chapter as the title piece of short fiction in a collection of Stoker's short stories under the name, "Dracula's Guest." "Dracula's Guest" makes no mention of Dracula nor does it mention any of the characters in the finished novel, but does have other ties to the novel. After the discovery of Stoker's notes and the republication of "Dracula' Guest" by McNally in 1974 in his own collection A Clutch of Vampires and by McNally and Florescu as part of the text in The Essential Dracula, the place of "Dracula Guest" in the development of Dracula became a hot topic for scholarly discussion.

Second, in order to secure the spectrum of rights to Dracula, Stoker created the first adaptation of the text by organizing a dramatic reading of it. Held in May 1897 with the participation of some of the members of Henry Irving's troupe (with whom Stoker worked professionally), the dramatic version of Dracula was hastily thrown together by taking two pre-publication copies of the novel and editing them into a dramatic text. Dialogue from the text was then assigned to those who assumed the role of the various characters. The performance of Dracula: or the Undead occurred only once and the text of the reading put aside until recently rediscovered and used for a centennial rereading and publication in 1997.

Third, simultaneously with the publication by Archibald Constable & Co. for the British public, Hutchinson & Co. published an edition for circulation through the British colonies around the world , the so-called Colonial edition. For many years, the few scholars who were even aware of plans to publish a Colonial edition believed that it had never been published. It was not listed in the British Library catalogue (or any other standard reference work where one might believe it would cited if it existed). However, in 2002, Robert Eighteen-Bisang located a copy and has subsequently announced its existence to the world. More importantly, in his paper, "Hutchinson's Colonial Library Edition of Dracula," he has made a compelling case that it may in fact be the true first edition.

During the remaining fifteen years of Stoker's life, additional alterations of the text would occur. Stoker lived to see the publication of the first American edition in which several changes, a few of some importance, were introduced. Then in 1901, the first translation of Dracula would occur, into Icelandic interestingly enough, and Stoker would write an "Introduction" for this edition. Finally, that same year, Constable would bring out an abridged edition of Dracula in an inexpensive paperback edition. Stoker would himself work on the abridgment, thus indicating to some extent what he considered the more and less essential parts of the text and storyline. In 1994, Transylvania Press reprinted the 1901 paperback edition, for which both Robert Eighteen-Bisang and historian Raymond T. McNally offered reflections on its significance.

Appendix: Christieís Description of the Dracula Manuscript (Auction of April 15, 2002)

Bottom of Form |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Section I. English-Language Publications

Dracula, the most important vampire novel of all time, has been in print ever since its appearance in 1897. As a new century of life for it begins, Dracula, now in the public domain, remains in print in some thirty different editions, and in more than two-dozen languages.

This work builds on two previous bibliographical explorations of Dracula:

Spehner, Norbert. Dracula: Opus 300. Montreal: Ashem Fictions, 1996. 68 pp. pb.

Eighteen-Bisang, Robert, and J. Gordon Melton. Dracula: A Century of Editions, Adaptations and Translations. Part One: English Language Editions. Santa Barbara, CA: Transylvanian Society of Dracula, 1998. 41 pp. pb. Staples.

However, this work takes a distinctly different approach. Editions have been grouped below so as to show the distinctive publishing history through which Dracula has passed. There are at least four distinct English texts of Dracula. The original text was issued almost simultaneously in 1897 by Archibald Constable & Co. (still considered the first edition by most) and by Hutchinson in what is termed a "Colonial" edition. This text is referred to below as the Constable text. In 1912, William Rider & Son obtained the British rights to Dracula. Rider reset the text and corrected some of the errors (typos) that existed in the Constable edition. Subsequently in England and through the former British colonies, the Rider text became the dominant text for new editions and reprints. At a later date, an associated Rider imprint, Jarrolds, published three editions (1966 to 1972). The Rider text would also be passed to their subsidiary, Arrow Books, at the beginning of the mass market paperback era. Editions in this tradition are listed below in chapter A. The British (Constable-Rider) Tradition.

There a was also a third British text, an abridged version of the Constable text issued once in 1901, an extremely important text, as Stoker himself did the abridgment. This text has been reprinted only once, in 1994 by Transylvania Press.

The same year that the Constable edition appeared, an American edition was issued by Doubleday (then Doubleday and McClure). This edition had several textual changes and the paragraphs were somewhat rearranged. In general, the Rider (British) may be distinguished from the Doubleday (American) text from the very first line of any given printing. The Rider text reads:

3 May. Bistritz. - Left Munich at 8.35 p.m. on 1st May. . .

The Doubleday text reads:

3 May. Bistritz. - Left Munich at 8:35 P.M., on 1st May. . .

The difference in citing time is, of course, of little significance in itself, however, it heralds a number of later variations in, for example, the merging and separation of paragraphs, and the single important and substantive alteration in the text. That alteration occurs in chapter four near the end of Harkerís diary entry for June 29. He is describing a conversation he overheard between the Count and the three women who also resided in the castle. In the English edition, Dracula says, "Wait. Have patience. Tomorrow night, tomorrow night, is yours!" while the American edition reads, "Wait! Have patience! Tonight is mine. Tomorrow night is yours!" The origin and meaning of this change, the American edition implying that Dracula will feed off of Harker, the only hint of Dracula feeding on a male, has become an issue in understanding the text.

Through the next sixty years, Doubleday continued to reissued copies of its American text. It also licensed editions to be printed by Wessels, Caldwell, Grosset & Dunlap, and finally the Modern Library. It issued a paperback text for the Armed Services during World War II and licensed the first mass market paperback edition as released by Pocket Books in 1947. The publications of the Doubleday text are cited below in chapter B. The American (Doubleday-Grosset & Dunlap) Tradition.

The arrival of Dracula into the public domain in 1962 (fifty years after the death of author Bram Stoker) prompted numerous reprintings of the three major texts by a variety of publishing houses. Most of these would come out as mass market paperbacks, but there would also be a number of omnibus editions that packaged Dracula with other horror classics and several annotated editions. The post-1965 editions are listed below in three chapters: D. Mass Market Paperback Editions; E. Omnibus Editions; and F. Annotated Editions.

Finally, brief passages from the Dracula text have been reprinted in a variety of very different collections of short fiction. These are listed below in chapter G. Excerpts Printed in Short Fiction Anthologies.

Citations

Each edition of Dracula in the English language is cited in the chapters below. Along with each edition, significant reprintings of that edition (especially those with variant covers and art work) are also noted. New editions are distinguished by a change of imprint (i.e. publisher), type face, and paging, and/or the addition of introductory essays and annotations. Reprintings are usually, but by no means always, listed on the back of the title page. Significant reprintings occur for paperback editions where cover art varies. In recent decades the name and artist of cover illustrations are often given. Also, hardback editions are frequently reprinted in a trade paperback variant.

With rare exceptions, reprints of Dracula have been issued under its standard name, but occasionally there have been variations. These most often occur when Dracula is included in an omnibus collection. Unless a different title is listed, one may assume that the title of any particular edition is simply Dracula.

For each edition, the standard bibliographical information is given. In addition, whether the particular printing is a hardback (hb.), trade paperback (tp.) or mass market paperback (pb.) is noted. Editions printed on 8&1/2" x 11" or larger size paper are cited as being of "large format."

If the edition contains additional information in the form of introductory essays, annotations, critical notes, bibliographies, or a biographical sketch of Bram Stoker, such material is listed and, where known, authors and editors cited.

Editions are frequently distinguished by their art work. A number of illustrated editions have appeared and are identified by the name of the artist. Of great importance since 1965, paperback printings have been distinguished by the variations in cover art. Where the name of a piece of cover art and the artist are known, they have been cited. Where unknown, the artwork has been briefly described. For example, the early paperback edition from Arrow was frequently reprinted and periodically the cover changed. For the paperback edition, simple reprintings are not cited except when a significant change in the cover has been noted.

I. English-language Editions of Dracula

A. The British (Constable-Rider) Tradition

1897

London: Hutchinson & Co., 1897. 392 pp. hb. Series: Hutchinson's Colonial Library. Issued for circulation in India, Australia, and other British colonies.

Westminster (London): Constable & Co., 1897. 390 pp. hb.

Rpt.: 1904

Rpt.: 1920

Rpt.: 1927

Rpt.: 1928.

1901

Westminster: Constable & Co., 1901. 138 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula crawling down castle wall.

Note: Abridged paperback edition.

1912

London: W. Rider & Son, 1912. 404 pp. hb. 9th ed., corrected

Rpt.: 1916.

Rpt.: 1921.

Rpt.: 1927. Green boards with black lettering.

Rpt.: 1928. dj: Color picture of Dracula climbing down castle wall.

Rpt.: 1931. (19th impression). Green boards with black lettering

Rpt.: 1947.

Rpt.: 1949.

Undated rpt.: dj: Dracula face emerging out of black background.

1947

London: Rider & Company, n.d. [1947]. 335 pp. hb. dj. Face of Dracula emerging out of black background.

1966

London: Hutchinson, 1966. 336 pp. hb.

Rpt.: 1975

Rpt.: 1978. Cover: Woman with crucifix, hand of Dracula.

London: Jarrolds, 1966. 336 pp. hb. Reprint of 1966 Hutchinson edition.

Rpt.: 1970. dj. Cover: Woman with crucifix, hand of Dracula.

2001

Chestnut Hills, MA: Elibron Classics/Adamant Media Corporation, 2000. 421 pp. tp. Cover: Street light with title in Grey. Reprint of Constable edition of 1987.

Rpt.: 2001. 421 pp. tp. Cover: Face of Dracula with prominent hypnotic eye.

B. The American (Doubleday-Grosset & Dunlap) Tradition

Included in this section are all of the hardback and trade paperback editions of Dracula issued by the Doubleday Company (under its various corporate expressions and imprints), and those editions published with licenses from Doubleday issued prior to Dracula's going into the public domain. [There is some question as to the status of the copyright and publishing rights enjoyed by Dracula in the United States as it was originally published in England and never registered with either the U.S. copyright office or Library of Congress. However, prior to 1962, American publishers operated as if Doubleday owned the copyright.]

While a large widely known publisher today, Doubleday had just been founded in 1897, the same year that Dracula was published in England. It was the brainchild of Frank Nelson Doubleday who with a partner, Samuel McClure, created the Doubleday & McClure Company in 1897. One year after the first American edition appeared in 1899, Walter H. Page replaced McClure as Doubleday's partner and the company became Doubleday, Page & Company. Then in 1927, Doubleday merged with the George H. Doran Company, resulting in the appearance of Doubleday, Doran, at the time the largest publishing concern in the English-speaking world. The business became known as Doubleday & Company in 1946.

Doubleday was sold to Bertelsmann, AG, a Germany-based worldwide communications company in 1986, and two years later was incorporated into the Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, which become a division of Random House Inc. in 1998. Doubleday continued it publication of Dracula into the twentieth-first century through the Modern Library and its several paperback affiliates, most notably Bantam Books.

Grosset & Dunlap, founded in 1898, developed a specialty in publishing books with movie tie-ins, hence an edition related to the Lugosi movie was a natural for it. In 1982, Grosset & Dunlap was purchased by G. P. Putnam's Sons, which in 1996 merged with the American Penguin publishing concern to become the Penguin Putnam Group.

New York: Doubleday & McClure, 1899. 378 pp. hb. Brown boards.

Note: First American ed.

New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1902. 378 pp. hb. Green boards with picture of Dracula with bat and wolf.

Rpt.: 1902. Red boards with picture of Dracula with bat and wolf.

Rpt.: 1903. Green boards with marbled cover.

Rpt.: 1904. Red boards with black lettering

Rpt.: 1904. Red boards with picture of Dracula with bat and wolf.

Rpt.: 1909. Tan boards with Dracula's castle.

Rpt.: 1913. Reddish brown boards with Dracula's castle

Rpt.: 1917. Greenish brown boards with Dracula's castle

Rpt.: 1919. Red boards with Dracula's castle.

Rpt.: 1920. Red boards with Dracula's castle

Rpt.: 1921. Red boards with gold stamp.

Rpt.: 1924. Red boards with gold stamp. (Lambskin Library),

Rpt.: 1925. Red boards with gold stamp.

Rpt.: 1926. Red boards with gold stamp.

Rpt.: 1926. Orange boards.

Rpt.: 1927. Red boards with gold stamp.

Rpt.: 1927. Orange boards.

Rpt.: 1928. Orange boards.

New York: A. Wessels, 1901. 378 pp. hb. White boards with green lettering and red and green garland decoration.

Note: Limited edition based on the Doubleday & McClure edition.

New York: A. Wessels Co., 1903. 378 pp. hb.

Note: Special limited ed.

New York: W. R. Caldwell, 1910. 378 pp. hb. Series: International Adventure Library.

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1928. 354 pp. hb.

Note: Dust jacket includes advertisement for Dracula stage play.

Undated rpt.: Black boards with red lettering.

Undated rpt.: dj: Woman in bed with head of Dracula in background.

Undated rpt.: dj: Woman in bed with pair of eyes in background.

Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, 1928. 378 pp. hb. Cover: Red boards with gold stamp.

Rpt.; 1929. dj: Man in evening dress with cape and cane.

Garden City, NY: Garden City Publishers, [1928]. 378 pp. hb. dj: Man in evening dress with cane and cape. Series: Sub Dial Library.

1930s

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1930. 354 pp. hb. Illustrated with stills from the Universal movie starring Bela Lugosi.

1932

New York: Modern Library, 1932. 418 pp. hb. Series: The Modern Library of the Worldís Best Books. New editions: 1996, 2001.

Undated reprint [1970]. hb. Series: The Modern Library of the Worldís Best Books, no. 31. Dust Jacket: Dracula, a face with three fangs.

Undated rpt.: Green boards with gold stamp Random House/Modern Library symbol.

Undated rpt.: Red boards with gold stamp Random House/Modern Library symbol.

Undated rpt.: Green boards with black square and gold stamp Random House/Modern Library symbol

Undated rpt.: Gray boards with black square and gold stamp Random House/Modern Library symbol.

Undated rpt.: Red boards without gold stamp Random House/Modern Library symbol Dust Jacket: Black with red and white lettering.

Rpt.: 1970. 417 pp. hb. Green boards. Series: A Modern Library book, M31.

Undated rpt.: [1983]. 418 pp. hb. Series: The Modern Library of the Worldís Best Books, unnumbered. Dust jacket: tan with no illustration.

Modern Library was the last company to obtain publishing rights of the Doubleday text of Dracula prior to its going into the free domain. It continues to keep the Doubleday text in print in an inexpensive popular edition. The Modern Library imprint was established in 1917 by the publishers Boni and Liveright. In 1925 Horace Liveright, sold the imprint to Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer. Two years later they founded Random House, and the Modern Library reprints of classic works of literature was henceforth an important part of Random House's annual sales.

1940s

New York: Nelson Doubleday, n.d. 354 pp. hb. Blue boards. dj: Glassine paper with embossed spider web design.

Undated rpt.: Black boards.

Undated rpt.: Red boards.

Dracula: A Horror Story. New York: Editions for the Armed Services, 1944. 447 pp. pb. Series: Armed Services edition, L‑25. Cover: "Published by arrangement with Doubleday, Doran and Co."

Rpt.: 1947. Series: Armed Services edition #851.

1950s-Present

Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, n.d.. 354 pp. hb. dj. Dust jacket: Black lettering on red background with white border.

Undated reprint: Dust jacket: white background with face of Dracula, drawn by Ben Feder. Black boards with blue lettering.

Garden City, NY: Garden City Books, n.d.. 354 pp. hb. Black boards with blue lettering on spine.

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1994. 522 pp. Series: Illustrated Junior Library. Cover by Larry Schwinger.

1996

New York: Modern Library, 1996. 419 pp. hb. dj. Series: The Modern Library of the Worldís Best Books, unnumbered. Includes brief biographical sketch of Bram Stoker, v-vii. Dust jacket: Bram Stoker.

2001

New York: Modern Library, 2001. 394 pp. tp. Series: Modern Library Classics. Intro.: Peter Straub, pp. ix-xxvi. Cover: Woman with cross necklace.

C. Dracula in the Late Twentieth Century

In 1962, Dracula entered the pubic domain. Three years later, the first wave of new editions and reprintings began to appear, especially as the paperback market blossomed. Different publishers used either the Rider or Doubleday text as they saw fit to produce new editions of Dracula for the library market (with reinforced binding that would withstand heavy use), large print editions for the visually impaired, enhanced and specialty printings for collectors, and cheap editions for mass public consumption. Listed below are the hardback and trade paperback editions. The mass market paperback editions are listed separately in chapter D. immediately following.

Since 1965, Penguin, Oxford, and Barnes & Noble have become major publishers of Dracula.

1965

New York: Limited Editions Club, 1965. 410 pp. hb. Slipcase. Oversize. Illustrated with wood engravings by Felix Hoffman. Introduction by Anthony Boucher. Doubleday text.

New York: Heritage Press, 1965. 410 pp. hb. Slipcase. Oversize. Illustrated with wood engravings by Felix Hoffman. Introduction by Anthony Boucher. Doubleday text.

Note: Reprint of Limited Editions Club ed.

Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1965. 410 pp. hb. Red boards with gold stamping. Series: The Collector's Library of Famous Editions.

Variant cover: Black boards with gold stamping.

1970

New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1970. 430 pp. hb. Introduction by James Nelson

1975

The Illustrated Dracula. New York: Drake, 1975. 184 pp. hb. Large format. Illustrations from 1931 Dracula movie (1931) montage. Doubleday text.

Rpt.: New York: Drake, 1975. 184 pp. pb.

Rpt.: New York: Chartwell Books, n.d. 184 pp. hb. dj: Bela Lugosi.

1976

Cutchogue, NY: Buccaneer Books, 1976. 382 pp. hb. Black boards. Doubleday text.

1981

New York: Amereon House, 1981. 402 pp. hb. Limited to 300 copies. Doubleday text.

Reprinted: 1986.

1983

Oxford [Oxfordshire]/New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. 380 pp. tp. Series: The World's Classics. Introduction (pp. vii-xix) and notes by Andrew Norman Wilson. Cover: Lugosi as Dracula (framed). Rider text.

Reprinted: 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990, 1991.

1991 printing-Cover: Bela Lugosi as Dracula (unframed)

1985

Parsippany, NJ: Unicorn Publishing House, 1985. 261 pp. pb. Edited by Jean L. Scrocco. Illustrated by Greg Hildebrant. Cover: Dracula with Lucy at Whitby. Doubleday text.

1988

London: Blackie, 1988. 379 pp. hb. Illustrator: Charles Keeping. Rider text.

1989

New York: Bedrick/Blackie, 1988. 379 pp. hb. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. Rider text.

1991

New York: Bedrick/Blackie: Book of the Month Club (BOMC), 1991. 379 pp. hb. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. Rider text.

1992

Dingle, Co. Kerry, Ireland: Brandon, 1992. 352 pp. tp. Cover: Shipwreck of the Demeter. Rider text.

New York: Barnes & Noble, 1992. 404 pp. hb. Series: Barnes & Noble Classics. Dust jacket: Bela Lugosi. Rider text.

1993

London: J.M. Dent/ Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1993. 382 pp. hb. Series: Everyman's Library.

Rept: 1994. Rev. ed. 1995. Rider text.

London: J.M. Dent/ Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1993. 382 pp. tp

Cover: Love by Gustav Klimt with gray border.

Thorndike, Me.: G. K. Hall, 1993. 609 pp. tp. Series: G. K. Hall Large Print Series. Cover Photo: Robert Darby. Doubleday text.

Oxford: ISIS Large Print Books, 1993. 609 pp. hb.

New York: Macmillan Library Reference, 1993. 592 pp. hb. Large print.

New York London: Penguin Books, 1993. 520 pp. hb. Series: Penguin Classics. Edited with an introduction and notes by Maurice Hindle. dj: Red on black. Rider text.

Dust jacket says: Guild America Books.

London, New York: Penguin Books, 1993. 520 pp. tp. Series: Penguin Classics. Edited with an introduction and notes by Maurice Hindle. Cover: Portrait of Henry Irving as Mephistopheles. Rider text.

New York, London: Penguin Books, 1993. 520 pp. tp. Series: Penguin Classics. Edited with an introduction and notes by Maurice Hindle. Cover: "Fin de siecle feminine evil" by Albert Pinot.

Ware, Hertsfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1993. 312 pp. hb. Series: Wordsworth Classics. Dust jacket: "A Moonlight Lake by a Castle" by Joseph Wright. Rider text.

1994

New York, London: Puffin Books (Penguin), 1994, 520 pp. tp. Series: Puffin Classics. Cover: A vampire by David Bergen. Rider text.

White Rock, BC: Transylvania Press, 1994. 337 pp. hb. Slipcase. Preface by Robert Eighteen-Bisang. Introduction by Raymond McNally.

Note: Limited edition reprint, in dust jacket, of 1901 abridged edition. Spelling errors and typos corrected.

1995

Philadelphia/London: Courage Books/Running Press, 1995. 518 pp. hb. Appendix: "from the Introduction to The Annotated Dracula" by Leonard Wolf, pp. 515-28. Dust jacket: Empty coffin with yellow border. Rider text.

Second printing: Dust jacket: Empty coffin with red border.

London: J. M. Dent/Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1995. 402 pp. tp. Series: Everyman's Library. Edited by Marjorie Howes. Cover: "Love" by Gustav Klint. Rider text.

1996

Dracula: The Definitive Edition. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1996. 427 pp. hb. Introduction by Marvin Kaye, pp. ix-xxi. Notes by Marvin Kaye. Illustrated by Edward Gorey. Postscript: " Bram Stoker: The Paradox of a Private Public Man" by Marvin Kaye, pp. 403-19.

K–ln: K–nemann Verlagsgesellschaft, 1995. 424 pp. hb. dj. Cover: Bela Lugosi as Dracula. Rider text.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. 389 pp. tp. Edited with introductory notes by Maud Ellmann. Cover: Bela Lugosi as Dracula. No picture on spine.

Cover variant, 1996: "Bram Stoker" in blue letters on yellow background, "Dracula" in white letters on blue background.

Cover variant, 1998: "Bram Stoker Dracula" in white letters on blue background.

Cover variant, 1998/1999: "Bram Stoker Dracula" in white letters on red background.

1997

New York: TOR, 1997. 383 p. hb. dj. Cover: Dracula and full moon by Boris Vallejo. Doubleday text.

1998

New York: Barnes & Noble, 1998 418 pp. hb. Series: Barnes & Noble Classics. dj: Graves in Snow by Caspar David Friedrich. Text taken from the Oxford University Classics Series (Oxford University Press, 1983)

New York: Barnes & Noble, 1998 418 pp. tp. Series: Barnes & Noble Classics. Cover: Whitby Abbey by Simon Marsden (detail).

Wickford, RI: North Books, 1998. 435 pp. hb. Publish on demand.

1999

Aust.: Sandstone Publishing, 1999. 418 pp. hb. dj. Cover: Whitby Abbey by Simon Marsden (detail). An Australian reprint of 1998 Barnes & Noble edition.

Canada: Prospero Classics Library, n.d. [1999]. 418 pp. hb. dj Graves in Snow by Caspar David Friedrich. A Canadian reprint of 1998 Barnes & Noble Edition.

2000

Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2000. 326 pp. tp. Series: Dover Thrift Editions.

New York: HarperCollins, 2000. 430 pp. hb. dj. Books of Wonder Series Illus: Barry Moser. Series Cover: Dracula with top hat.

2001

Denver: Micawber Fine Editions, 2001. 356 +xvi pp. hb. Slipcase. Illus.: Geoff Jones. Afterword: R. L. Dean. Limited to 65 copies.

2002

Doylestown, PA: Wildside Press, 2002. 324 pp. hb. Cover: Christopher Lee as Dracula. Doubleday text.

Rpt.: tp.

D. Mass Market Paperbacks

Prior to Dracula's going into the public domain, mass market paperback edition appeared from Arrow Books (the paperback subsidiary of Rider & Co.) and Pocket Books (continuing the Doubleday edition). After Dracula entered the public domain, several of the larger paperback publishers issued new editions and many of the smaller companies have followed suit. The 1979 Universal remake of Dracula starring Frank Langella, the Francis Ford Coppala remake in 1992, and the 1997 centennial of the first publication of Dracula each prompted multiple new popular editions of the book.

New York: Pocket Books, 1947. 409 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula hovering over female in bed. "Dracula: the most famous horror story ever told."

Notes: First pocketbook edition.

London: Arrow, 1954. 336 pp. pb. Rider text.

Reprinted: 1957, 1958, 1959, 1962, 1965, 1967, 1969

1957 Cover: Face of Dracula, red border.

1958 Cover: Dracula with castle in background.

1959 Cover: Dracula with castle in background.

1962 Cover: Dracula in coffin with bat.

1967 Cover: Dracula in coffin.

New York: Permabooks, 1957. 376 pp. hb. Cover: "Dracula: the most famous horror story ever told."

Undated reprint. Cover: Christopher Lee/Dracula with female.

New York: Signet Books/ New American Library, 1965. 382 pp. pb. Series: Signet Classic. Cover: skull/bat design. "A Masterpiece of Gothic HorroróThe Nightmare Story of the Dread Master of the Un-dead." Doubleday text.

Reprinted: 1965, 1974, and in undated copies. Prices vary from 60 cents to $1.25.

1965 reprint: Series: Signet Classic. Cover: skull/bat design. "The Dread Lord of the Un-deadóA Masterpiece of Gothic horror"

Undated reprint. Cover: Tree in the forest

1998 reprint. Cover: Castle Dracula. "100th Anniversary Edition."

New York: Airmont, 1965. 317 pp. pb. Introduction by A. W. Lawndes. Cover: Dracula montage. Doubleday text.

New York: Dell Books, March 1965. 416 pp. pb. Series: Laurel Leaf Library.

Cover: Profile of Dracula in an oval.

Reprinted: 1967, 1968, 1970, October 1970, February 1971, September 1971, January 1972, May 1972 (9th printing), October 1972, January 1973, June 1973, November 1973, March 1974, July 1974, October 1975, October 1975, April 1977, June 1978, 1980, October 1981 (21st printing), February 1985 (22nd printing).

.

New York: Pyramid Books, 1965. 352 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula and bat with white background.

Variant cover, 1972. Dracula and bat with red background. Doubleday text.

London: Arrow, 1970. 384 pp. pb.

Reprinted: 1971, 1973.

1973 printing. Cover: Woman with crucifix, hand of Dracula

New York: Magnum Easy Eye/Lancer Books, 1970. 558 pp. pb. Cover: Bela Lugosi as Dracula, without border. Doubleday text.

Variant cover: Bela Lugosi as Dracula with border.

London: Arrow Books, 1974. 336 pp. pb. Rider text. Cover: Dracula with female victim. Rider text.

Reprinted: 1979.

London: Sphere, 1974. 382 pp. pb. Series: The Dennis Wheatley Library of the Occult, vol. 1. Cover: Womanís face inside of zodiac. Rider text.

New York: Tempo Books/Grosset & Dunlap, 1974. 508 pp. pb. Large type. Cover: Picture of Dracula draped with cape. Doubleday text.

Reprinted: 1979

Harmondsworth, London, New York: Penguin Books, 1979, 1992. 448 pp. pb. Cover: Hand coming out of a coffin. Reprint occasioned by Universal's Dracula starring Frank Langella. Rider text.

Undated reprint: Cover: Candle and Flame. "The Original Classic, now a Major Motion Picture."

Note: Penguin was founded in the mid 1930s and was one of the original paperback book publishing houses. In 1970, it was acquired by Pearson, the international media group, and underwent major internal changes. Its first edition of Dracula appeared the next year occasioned by Universal's new Dracula staring Frank Langella. It has subsequently released a variety of Dracula editions, including several from its subsidiary for juvenile titles, Puffin Books and adaptations form those learning English.

New York, Harmondsworth, London: Penguin Books, 1979. 449 pp. pb. Cover: Hand coming out of a coffin, with additional text, "Bram Stoker's original Dracula. The tale of horror and passion. . . Now a major motion picture." Reprint occasioned by Universal's Dracula starring Frank Langella.

Reprinted: 1994.

London: Arrow Books, 1979. 336 pp. pb. Rider text. Cover #1: Bat with title in silver

Simultaneous reprint: Cover #2: Bat with title in black. Reprint occasioned by Universal's Dracula starring Frank Langella.

London: Coronet Books, 1979. 352 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula/Frank Langella poster. Doubleday text. Reprint occasioned by Universal's Dracula starring Frank Langella.

New York: Jove, 1979. 352 pp. pb. With illustrations of Frank Langella as Dracula, from the 1979 Universal movie. Doubleday text. Cover: Dracula/Frank Langella poster.

New York: Tempo Star/Ace/Grosset & Dunlap, 1974/1979. 508 pp. pb. Doubleday text.

Cover: Dracula at staircase in castle

London, Toronto, New York, Sydney: Bantam Books, 1981. 402 pp. pb. Series: Bantam Classic. Introduction by George Stade. Cover: "Oh, Whatís That in the Hollow" by Caspar David Freidrich.

Reprinted: annually, 9th printing 1989.

9th printing (1989). Cover: "Man and Woman Contemplating the Moor" by Caspar David Freidrich

Rpt.: London, Toronto, New York, Sydney: Bantam Books, Econo-Clad-Books, 1981. 402 pp. hb. Series: Bantam Classic. Introduction by George Stade. Cover: "Oh, Whatís That in the Hollow" by Caspar David Freidrich.

Mahwah, NJ: Watermill Press, 1983. 414 pp. pb. Cover: Bust of Dracula. Doubleday text.

Undated reprint: Cover: Dracula as bat-like creature

London/New York: Puffin Books, 1986. 447 pp. tp. Series: Puffin Classics. Rider text.

Reprinted: 1994.

1988 printing. Cover: Smiling Dracula

New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1988. 368 pp. pb. Introduction: "The Life of Bram Stoker" by R. L. Fisher, pp. vii-viii. Foreword (pp. ix-x) and Afterword (pp. 367-8) by R. L. Fisher. Cover: Dracula in bedroom. Doubleday text.

Reprinted: 1989.

Rpt.: New York: Aerie Books, Ltd./Tom Doherty, 1988. 368 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula in bedroom.

Rpt.: [New York]: Aerie Books, Ltd./[Tom Doherty, 1988]. 368 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula and full moon with special Wal-Mart sale seal.

New York:. Tom Doherty Associates, 1989. 368 pp. pb. Cover: Dracula and full moon by Boris Vallejo. Title embossed in blue.

Undated reprint: Title in red.

New York: Signet Classics, 1992. 382 pp. pb. Introduction, "Returning to Dracula" by Leonard Wolf, pp. i-xi. Cover: Victim of cholera buried prematurely in coffin, painting by Antoine-Joseph Wiertz.

Rpt.: November 1992. 382 pp. pb. Introduction: "Returning to Dracula" by Leonard Wolf, pp. i-xi. Cover: Dracula gargoyle. Includes illustrations from Francis Ford Coppolaís Bram Stokerís Dracula.

Rpt. 1997

London: Pan, 1992. 382 pp. pb. Cover: Gargoyle from Francis Ford Coppola movie. Doubleday text.

Introduction: "Returning to Dracula" by Leonard Wolf.

Ware, Hertsfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1993. 335 pp. pb. Series: Wordsworth Classics.. Cover: "A German Landscape" by Hermann Koekkoek. Rider text.

Reprinted: 1994, 1995. 1993 printings had variations on title: black on yellow and white and white on black.

1994 printing. Title imprint: black on yellow.

London/New York: Penguin Books/Godfrey Cave Edition, 1994. 447 pp. pb. Series: Penguin Popular Classics. Cover: Print of Dracula and young girl. Rider text. Printed in England.

Rpt.: [1999]. Cover: Bela Lugosi as Dracula. Printed in England.

Hereford, UK: Hay Classics, 1994. 377 pp. pb. Series: Hay Classics. Cover: "The Abbey Under the Oak Tree" by Caspar David Friedrich. Doubleday text.

Dracula Unleashed: The Official Strategy Guide & Novel by Rick Barba. Rocklin, CA: Prism Publishing, 1994. 384 pp. tp. Volume includes complete Doubleday text of novel; with accompanying cd.

New York: Scholastic, Inc., 1999. 502 pp. pb. Introduction by Walter Dean Myers. Scholastic Classics Series Cover: Dracula emerging from coffin. Doubleday text

E. Annotated Editions

The Essential Dracula: A Completely Illustrated and Annotated Edition of Bram Stokerís Classic Novel. New York: Mayflower, 1979. 320 pp. hb. Oversize. Notes: Ed. by Raymond T. McNally and Radu Florescu. Includes text of "Dracula's Guest" Cover: Frank Langella as Dracula. Doubleday text.

Rpt.: London: Penguin, 1993. 320 pp. tp.

The Annotated Dracula. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1975. 362 pp. hb. Large format. Annotated by Leonard Wolf. Based on original 1897 Constable text.

Cover: Dracula's castle.

Rpt.: New York: Ballantine, 1976. 362 pp. tp. Cover: Dracula in coffin.

Note: this is the first edition of Dracula to include the text of "Dracula's Guest."

Dracula Unearthed. Westcliff-on-the-Sea, Essex, UK: Desert Island Books, 1988. 512 pp. hb. dj. Annotated and edited by Clive Leatherdale. Cover: Representation of Dracula.

The Essential Dracula: including the complete novel by Bram Stoker. New York/ London, Plume, 1993. 484 pp. tp. Edited by Leonard Wolf. Cover: Nosferatu (Count Orlock).

Note: revised edition of the Annotated Dracula (1974)

Dracula. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997. 488 pp. tp. Series: Norton Critical Editions. Edited by Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal. Cover: Portrait of Henry Irving as Mephistopheles, gray border with white lettering.

Additional critical material in this edition includes: Roth, Phyllis A. "Suddenly Sexual Women in Bram Stoker's Dracula" (pp. 411-21); Senf, Carol A., ed. "Dracula: The Unseen Face in the Mirror" (pp. 421-31); Moretti, Franco. "A Capital Dracula" (pp. 431-44); Craft, Christopher. "'Kiss Me with Those Red Lips': Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker's Dracula" (pp. 444-59); Dijkstra, Bram. "Dracula's Backlash" (pp. 460-62); Arata, Stephen D. "The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization" (pp. 462-70); Schaffer, Talia. "A Wilde Desire Took Me: A Homoerotic History of Dracula" (470-82). Addition materials include a selected, bibliography, filmography, and list of dramatic adaptations.

8th printing. Cover: Portrait of Henry Irving as Mephistopheles, white border with black lettering.

Dracula. Peterborough, ON, Ca: Broadview Press, 1998. 493 pp. tp. Series: Broadview Literary Texts.

edited by Glennis Byron. Cover Photo of visitors to International Exhibition held in London in 1862.

Dracula. Boston: Bedford/New York: St. Martin's, 2002. 622 pp. tp. Ser: Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism. Ed. by John Paul Riquelme. Cover: Caspar David Friedrich, Epitaph for Johann Emanuel Bremer.

F. Omnibus editions

These volumes contain the complete text of Dracula, plus the complete text of one or more other novels.

The Horror Omnibus. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, n.d.[1930s] 354 pp. + 240 pp. hb. Dust jacket: Skeleton and woman with orange background. Cover says: "Two Famous Novels of the Supernatural, Complete in One Volume/ "Dracula" by Bram Stoker/"Frankenstein" by Mary W. Shelley. Reprints Grosset & Dunlap edition of Dracula.

Note: The only omnibus edition of Dracula prior to the text going into the public domain. It included Frankenstein, which had already been in public domain for some decades. Grosset & Dunlap specialized in books with movie tie-ins.

Dracula/Frankenstein. Garden City, NY: Nelson Doubleday, [1973]. 655 pp. hb.

Dracula/Frankenstein. Garden City, NY: International Collectorís Library, n.d. [1973?]. 655 pp. hb. Cover: Green with gold lettering.

Notes: Reprint of 1973 Nelson Doubleday omnibus edition.

Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll & Mister Hyde, & Dracula. New York: New American Library/Signet Classic Books, 1978. 211/382/70 pp. pb. Introduction by Stephen King. Cover: Mask of Frankenstein, Dracula, and Mr. Hyde.

10-20 printings (undated): Cover: Sunset landscape.

21st printing: Cover: Graveyard.

Reprinted as: Three Classics of Horror. London: Penguin Books, 1988. 211/382/70 pp. pb. Cover: Medusa head.

Dracula & The Lair of the White Worm. London: W. Foulsham Books and Co., 1979. hb. Rider text.

Classic Horror Omnibus Volume 1. London: New English Library, 1979. 653 pp. hb. dj.

Collected fiction includes: Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Werewolf, and The Phantom of the Opera.

A Treasury of Gothic and Supernatural. New York: Avenal Books, 1981. 707 pp. hb.

Collected fiction includes: The Castele of Otranto, Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and The Turn of the Screw.

Dracula and the Lair of the White Worm. London: Guild Publishing/Book Club Associates, 1986. hb. dj. Introduction: Richard Dalby. Cover: Dracula with moon as halo.

Dracula/Frankenstein. Leicester: Gallery Press, 1988. 404/242 pp. hb.

Classics of Horror. Stamford, CT: Longmeadow Press, 1991. 655 pp. hb. Cover: Gold on black simulated leather.

Note: Includes Dracula and Frankenstein.

Classics of Horror. Stamford, CT: Longmeadow Press, 1991. 654 pp. tp.

Notes: Includes: Dracula and Frankenstein.

Dracula/Frankenstein. New York: BOMC/QPBC [Quality Paperback Book Club], 1991. 616 pp. tp. Cover: Gray background with drawing of Dracula and Frankenstein's monster.

Bram Stokerís Dracula Omnibus. London: Orion, 1992. 576 pp. hb. Introduction by Fay Weldon. Cover: Face of Dracula. Rider text.

Rpt.: London: Orion, 1992. 576 pp. tp. Cover: Face of Dracula.

Rpt.: Smithbooks, 1992. 543 pp. hb. Introduction by Fay Weldon. Cover by George Underwood.

Rpt.: New York: Chartwell Books, 1994. 576 pp. hb. Dust jacket and cover: Face of Dracula. Rider text.

Horror Classics. London: Chancellor Press, 1993. 527 pp. hb. Cover: Dracula. Rider text.

Collected fiction includes: Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Horror Classics. Stamford, CT: Longmeadow, 1994. 527 pp. hb. Dust jacket/Cover: Dracula in profile with Frankenstein in background. Rider text.

Collected fiction includes: Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Dracula and Frankenstein. New York: Smithmark Publishers, 1995. 498 pp. hb. Illustrated by Brian Lee.

Collected fiction. Juvenile.

A Gothic Treasury of the Supernatural. New York: Gramercy Books/Avenel, 1995.707 pp. hb.

Note: Reprint of A Treasury of Gothic and Supernatural (1981).

Rpt.: London: Leopard Books, 1981 [1995].

Four Classic Thrillers. New York: Bantam Books, 1996. pb. Four-volume boxed set that includes the Bantam edition of Dracula.

The Classics of Horror. Ann Arbor, MI: State Street Press, n.d. [2001]. 655 pp. hb. Cover. Gold on black design. Collected fiction: Dracula and Frankenstein.

The Library of Classic Horror Stories. Philadelphia: Running Press/Courage Books, 2001. 1045 pp. hb. dj. Jacket cover: Gil Cohen. Collected fiction: Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Body Snatcher, Markheim, the Island of Dr. Moreau, and stories of Edgar Allan Poe.

Williams, Anne, ed. Three Vampire Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 200-, 481 pp. hb. This edition includes Dracula, "The Vampyre" by John William Polidori, and "Carmilla" by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. It is the first occasion of "Carmilla" and Dracula being published in the same volume.

G. Excepts printed in Short Fiction Collections

Book of Horror Stories. London: Black Cat, 1987. 192 pp. hb. boards. Includes excerpt from Dracula, pp. 93-109.

Classic Erotic Tales. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 1994. Excerpt from Dracula, pp. 143-46. Dust jacket: detail of Dreaming by Paul Francois Quinsac.

Jarvis, Mike, and John Spencer, ed. Echoes of Terror. Secacus, NJ: Chartwell Book, 1980. 96 pp. hb. dj. Dust jacket: Drawing by Gordon Crabb of a woman in a cemetery.

Gladwell, Adele Olivia, and James Havoc, eds. Blood and Roses: The Vampire in 19th Century Literature. London: Creation Press, 1992. 283 pp. tp. Excerpt from Dracula, pp. 281-3.

Rev. ed.: London: Creation Books, 1999. 286 pp. tp.

Haining, Peter, ed. The Vampire Huntersí Casebook. London: Warner Books, 1996. 363 pp. tp. "'The Way of the Vampire' by Professor Abraham Van Helsing," pp. xv-xix.

Rpt.: New York: Barnes & Noble, 1996. 363 pp. hb.

Lee, Christopher Lee, and Michel Parry, eds. The Great Villains: an Omnibus of Evil. London: W. H. Allen & Co, 1978. 255 pp. hb. dj. Excerpt from Dracula, pp. Dust jacket: Drawing by Bob Haberfield, man in cape and top hat on a cobblestone street. Excerpt from Dracula, pp. 176-207.

Skal, David J., ed. Vampires: Encounters with the Undead. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2001. 604 pp. hb. dj. Large format. An anthology of fiction and nonfiction. Excerpt from Dracula, pp. 211-21.

Victorian Erotic Tales. London: Michael O'Mara Books, 1995. Excerpt from Dracula, pp. 229-31.

Volta, Ornella, and Valeria Riva, eds. The Vampire: An Anthology. Introduction by Roger Vadim. London: Neville Spearman, 1963. 286 pp. hb. Includes excerpt: "The Death of Dracula."

Rpt.: London: Pan Books, 1965. 316 pp. pb. Cover: Women with stake in heart. Cover banner: "All the best vampire stories in the world."

2nd Pan printing: 1971.

3rd Pan printing: 1972. No cover banner.

Youngson, Jeanne, ed. The Count Dracula Fan Club Book of Vampire Stories. Chicago: Adams Press, 1980. 91 pp. pb. Includes: "Chapter Two from Dracula," pp. 67-87.

Appendix I: Hutchinsonís Colonial Library Edition of Dracula.[i]

By Robert Eighteen-Bisang

Introduction

This is a preliminary report about a hitherto lost edition of the worldís most famous and influential vampire novel.

Hutchinsonís Colonial Library edition of Dracula not only states the date ì1897î on its title page, but was almost certainly printed simultaneously with ñ i.e., before or shortly after ñ the first Constable printing.

Bram Stoker drew up an undated ìMemorandum of Agreementî for the publication of Dracula (which was titled ìThe Un-Deadî in early drafts) which his publisher, Archibald Constable and Company, typed up and revised. Both parties signed the final contract on the 20th of May 1897.[ii]

It states that: ìThe Author having written a work called the ìUN-DEADî and being prior to the signing of this agreement possessed of all the rights therein agrees with the Publishers for its publication in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Dependencies (Canada being excepted).ì

The contract makes explicit provisions for a colonial edition. Part 5 declares: ìThe Publishers may with the consent of the Author print and sell a colonial edition (Canada being excepted from the operations of such editions).î

Until now, it had been assumed that the publisher did not exercise this option because no copy of a colonial edition had been found.

Hutchinsonís Colonial Library edition of Dracula is not listed in the British Library Catalogue, The National Union Catalog, Worldcat or in any standard reference work on fantasy or horror, including: Ashley, Barron, Bleiler, Clute, Frank, Locke, Reginald, Tuck, Tymn or Wolff. Graeme Johansonís A Study of Colonial Editions in Australia: 1843-1972 does not make any reference to it, and there is not even a hint that it exists in thousands of studies about Bram Stoker, Dracula or vampires.

A brief description of the colonial edition is in order:

STOKER, BRAM. Nee: Abraham Stoker, Jr. b. November 8, 1847. d. April 20, 1912.

DRACULA. London: Hutchinson & Co, 1897. [i-vii] viii-ix [ix] [1] 2-390 [391-392] pp. hb. with dark-red binding and gilt lettering. Hutchinsonís Colonial Library Series. Issued for circulation in India and the British Colonies.

The particular features of the copy that was purchased on E-Bay in Auction #1456726870 from Pioneer Books of Melbourne, Australia on August 23, 2001 include:

An old catalog number [ìF.433.î] appears on the title page and on page one, and there are three library stamps [ìTEA TREE GULLY INSTITUTEî] in the text. The binding has moderate stains, with a large, light stain on the cover and scattered, internal markings. The lettering on the cover and spine is faded. The binding is almost entirely detached from its hinges. This copy is missing the front endpaper, and all but a small piece of the leaf that follows the text [pp. 391-392] has been torn out. However, the rear endpaper is intact and the text is complete, including the printer's colophon.

The previous owner recalls that he obtained it ìa very long time ago,î but cannot furnish any additional information.

Tea Tree Gully is northeast of Adelaide. The area was settled in 1857, and re-named ìTee Tree Gullyî in October of 1858. The Australian Handbook of 1904 tells us that it had ìan institute,î and, at this point, it can be assumed that this institution existed in 1897.

The following comparison of the domestic and colonial editions uses a presentation copy of Dracula ñ i.e., one of a handful of early copies that is distinguished by the embossment ìPresented by Archibald Constable & Coî on its title page ñ as the basis of comparison. Any differences between these editions are noted in the right-hand column:

Archibald Constable and Company Hutchinson & Co.

Cover: Mustard-yellow binding with red Dark red binding with gilt lettering.

lettering and a red rule.

Cover says: Dracula / By / Bram Stoker HUTCHINSONíS COLONIAL LIBRARY is printed in the top right-hand corner.

Spine says: Dracula / By / Bram Stoker / DRACULA / BRAM STOKER /

Constable / Westminster[iii] HUTCHINSONíS COLONIAL LIBRARY

No dust jacket. As issued?[iv]

Size: 8vo. ñ i.e., 7 æ ì by 5 º.ì

Collation and binding: a. 16-page signature

sheets with one 8-page signature at the

front of the book. b. Edges of pages

untrimmed. c. Bound by hand.

a. Free front endpaper ñ blank recto. a and b. Note: Missing leaf. Torn out?

b. Free front endpaper ñ blank verso.

c. Half-title page: DRACULA / BY / BRAM

STOKER

d. Catalog: BOOKS BY THE SAME

AUTHOR. / Under the Sunset.î / ìThe

Snakeís Pass.î / ìThe Waterís Mou.î /

ìThe Shoulder of Shasta.î

e. Cancelled title page: DRACULA / BY e. HUTCHINSONíS COLONIAL LIBRARY /

BRAM STOKER / WESTMINSTER / DRACULA / By / BRAM STOKER / London: /

ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND HUTCHINSON & CO. / 34 PATERNOSTER

COMPANY / 1897 ROW / 1897

f. Copyright page: ìCopyright, 1897, in the f. This edition is issued for circulation / in

United States of America, according / to India and the British Colonies / only.

Act of Congress, by Bram Stoker. / [All

rights reserved.]

g. Dedication page: TO / MY DEAR

FRIEND / HOMMY-BEG

h. Blank verso.

i. Contents page.

viii. Contents continued.[v]

ix. Contents concluded.

[x]. Text: ìHow these papersÖî Eight

lines. This is usually assumed to be

part of the text.

[1]. a. Beginning of text. b. A printerís mark ñ

ìBî ñ in the bottom right-hand corner.[vi]

2. First numbered page of text.

17. Printerís mark: ìCî.

385. Printerís mark: ì2 Cî.

389. End of text.

390. a. ìNote / When we gotÖ ì Eighteen

lines. This is usually assumed to be

part of the text. b. Printerís colophon:

HARRISON &SONS, Printers in

Ordinary to Her Majesty, St. Martinís

Lane.

[391]. Free flypaper ñ blank recto.[vii] [391-2]. Note: Most of this leaf has been torn

[392]. Free flypaper ñ blank verso. out, but the remaining fragment appears to be

an integral part of the final signature.

[393]. Free rear endpaper ñ blank recto.

[394]. Free rear endpaper ñ blank verso.

Constable

The features of any particular edition can often be understood by referring to other editions and the conditions that gave rise to them. On one hand, the discovery of a colonial edition creates a host of new problems. On the other, it can be likened to an important piece in a jigsaw puzzle.

Dracula is a bibliographic nightmare.

To begin with, there is an extensive pre-textual stage that includes: ìBram Stokerís Original Notes and Data for his Dracula,î[viii] a copy of his manuscript (The Un-Dead),[ix] a story (ìDraculaís Guestî)[x] and a play.

Prior to the publication of the novel, the author rewrote it as a play to establish his copyright. Dracula: or the Un-Dead was presented to a small group of employees and passers-by at the Lyceum Theatre on Tuesday the 18th of May at 10:15 a.m.[xi]

The fact that the final contract for Dracula was signed two days later may be indicative of the planning that gave life to Stokerís creation.

There are also four seminal texts. In addition to the original wording of 1897, both Doubleday & McClure[xii] and William Rider[xiii] made minor changes in the text when they created new editions of Dracula in 1899 and 1912. However, wholesale revisions occur in the abridged paperbound text of 1901 in which Stoker abridged his novel for Constable's Sixpenny Series.[xiv]

Despite the challenges that these variations offer bibliographers, each of them enriches our understanding of the text and the authorís intentions in certain ways.

No one knows when the first edition of Dracula was published. Possible dates range from late May to late June. In a letter to William Gladstone on ìMay 24/97,î Stoker wrote, ìMay I do myself the pleasure of sending you a copy of my new novel Dracula which comes out on the 26th.î It appears that his letter was accompanied by a copy of Dracula. If so, presentation copies must have been flying about no later than May 21st. Otherwise, Barbara Belfordís claim that ìDracula arrived at the booksellers on May 26, 1897î may be correct.[xv] Other candidates include June 2nd and June 10th. Peter Haining and Peter Tremanyne, who were granted access to Constableís archives, champion the date of ìThursday, 24 June 1897Ö with the first copies destined for the literary editors of the major national newspapers and magazinesî (but do not provide any evidence of this).[xvi]

No matter when Dracula was first published, it was printed in some form well before any of these dates. The original copy of the play ìÖ is partly hand-written and partly pasted into place in sections cut from two proof copies stamped by Harris [sic] and Sons, Printers (a firm of bookbinders based in London).î[xvii]

Every page bears Stokerís mark. Despite his hurried, often almost illegible handwriting, he put considerable thought into how his novel could best be reworked for the stage. Given the fact that his duties as Irvingís assistant left him little time to write, this task must have taken a month or two. If we split the difference, we can conclude that Dracula had been typeset by the middle of April 1897.

To the dismay of both collectors and dealers, Constable does not identify first editions or distinguish reprints in any systematic way. Early printings of Dracula announce the date ì1897î on the title page, but do not contain a statement of edition. (The first one to do so is the ìFifth Editionî of ì1898.î) Therefore, collectors and book dealers have had to rely on other means to determine which edition came first.[xviii] A rule of thumb is ìthe more advertisements, the later the edition.î Evidence from presentation copies and signed editions proves that the ìfirst editionî has a cancelled title page and does not contain any advertising material after the text, while the second has an advertisement for The Shoulder of Shasta on page [392]. The third and fourth editions went through several printings. A few copies do not have a cancelled title page, and at least one has a cancelled dedication page. There are also variations in the texture of the cloth, the thickness of the paper and the number of advertisements. They usually have an ad for The Shoulder of Shasta followed by a catalog of 8, 10 or 16 pages. Differences in the contents and placement of this material abound. For example, there are both full and half-page ads for Dracula.

The only possible conclusion is that Dracula went through numerous printings, and was bound in small lots with whatever materials were available at the time. The fact that it was bound by hand makes this relatively easy to do.

Colonial Editions

From the middle of the nineteenth century, colonial editions were distributed to four main areas: Africa, Australia, Canada, and India. In addition to providing publishers with an additional source of profit, they offered countries that did not have a large enough population to support a local publishing industry opportunities to enjoy a wide range of literature.

According to Graeme Johanson, ìThe most important feature of the printing of colonial editions was that it was totally integrated with the printing of original editions, or it was done from stereotype plates made from settings for first or other editionsî.[xix]

Findings

٭ The only observable differences between the Constable and Hutchinson editions are the binding, the copyright page and the title page.

٭ Both editions were printed from the same plates, and use the same signature sheets. Even the printerís marks are identical.

٭ Both editions were printed by the same printer. Harrison & Sons produced the first eight editions of Dracula. They printed at least seven editions for Archibald Constable and Company from 1897 to 1899, and one for Hutchinson & Co. in 1897. In contrast, the Eighth Edition of 1904 was printed by Butler & Tanner of Frome and London.[xx]

٭ The Hutchinson Colonial Library edition is the only other edition that states ì1897î on its title page. The fact that it has a cancelled title page leaves no doubt that it was published in the same year as the first Archibald Constable edition (In contrast, many subsequent editions of Dracula reproduce all or part of the original copyright notice on their copyright pages. Reprints that do not state the year in which they were published or number their editions have caused some confusion. More than one collector who has acquired a copy by a publisher such as Doubleday or Grosset & Dunlap has been convinced that they have acquired a first edition.)

٭ Colonial editions were always printed in conjunction with their domestic counterparts. Indeed, as Graeme Johanson points out: ìÖ the main purpose of ècolonialsí was to release new novels simultaneously at home and abroad, and publishers achieved this by use of run-on sheets or stereotype plates.î[xxi] In many cases, ìThe ècolonialsí were shipped to Australia weeks in advance of British release to allow a common publication date, and hence were, in effect, the first issues of particular editions.ì[xxii]

٭ Concomitantly, the colonial edition is either the first or second edition of the best-selling novel in the world.

٭ In either case, it stands as the first edition by a publisher other than Constable. (This also means that the first American edition of Dracula, which was brought out by Doubleday & McClure in 1999, falls into third place.)

٭ Hutchinsonís edition is the missing link in a series of colonial editions of Bram Stokerís novels. His previous novel, The Shoulder of Shasta, was published by Archibald Constable & Co. in 1895, and a colonial edition was published by Macmillan and Co. the same year as ìNo. 230î in Macmillanís Colonial Library Series. Richard Dalbyís Bram Stoker: a bibliography of first editions, also tells us that The Jewel of Seven Stars of 1903, The Man of 1905, Lady Athlyne of 1908 and The Lady of the Shroud of 1909 were all published ìsimultaneouslyî by Heinemannís Colonial Library.

٭ It is possible that Constable choose Hutchinson as the publisher of the colonial edition of Dracula, because they had recently taken on Marie Corelli, whose weird occult thrillers made her the best-selling author in the world.

٭ Hutchinsonís colonial edition precedes Rider and Companyís by half of a century.[xxiii]

٭ This is the first edition by the Hutchinson, Rider, Arrow, Jarrolds group (now owned by Random House), which assumed the British rights to Dracula in 1912.

٭ The pasted in title page in early Constable editions of Dracula has often been attributed to the fact that the title was changed shortly before the novel was published. However, this problem could have been solved by re-typesetting one page of the first signature. With the discovery of the colonial edition, the mystery of the inserted leaf (i.e., the title page and copyright page) can be seen as an economical way to print the text, insert whatever indicia is called for, and bind the book accordingly. Of course, this operation would have to have been planned before the first eight-page signature was typeset.

Further Research

Our most important task is to find a copy of the colonial edition with pages [391] and [392]. Although there is usually no correlation between the advertisements in domestic and colonial editions, a date code in the catalog of the colonial edition of The Shoulder of Shasta shows that it preceded the Constable edition by three months. The missing leaf in the copy that has be used for comparison could be blank, but it could also contain an ad for The Shoulder of Shasta or a surprise that is awaiting discovery.

In addition to the Australian edition, there could be an African or Indian impression, or even a (non-colonial) Canadian edition of Dracula.

Bram Stokerís contract with Constable called for ìat least three thousand copies.î Given the rarity of Hutchinsonís Colonial Library edition and the fact that Australia had about one tenth as many people, it may have received as little as 300 copies.

Search colonial libraries for records of this copy, and the dates on they were received. In 1897, it took about five weeks for a shipment to reach Australia, and a week or more to reach many destinations. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the value of any such records in advance. Of course, this also applies to reviews in newspapers or magazines.

The fact of a colonial edition also implies the existence of contracts, royalty statements, advertising material and other materials.

It appears as if the colonial edition was printed in London, but we do not know if the sheets were bound before they were shipped to the colonies. (In either case, this could explain why Constableís first printing does not proclaim itself the ìfirst edition.î) It is also possible that the sheets for colonial edition were printed at the beginning of the print run, but released at the same time as or later than Constableís edition.

In conclusion, I would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of Richard Dalby, L. W. Currey, Mark Dwor LLD, Graeme Johanson, Brenda Peterson, Pioneer Books, the North-West Book Company, Michael Thomson and White Dwarf Books. Of course, I am responsible for any mistakes in the use or interpretation of the data that they provided. A special note of thanks is due to David Niall Wilson, who discovered Hutchinson's Colonial Library edition of Dracula on E-Bay and brought this rara avis to my attention.

AppendixII: The 1901 Paperback Edition of Dracula

Introductory material from the 1994 Reprint

Foreword

Archibald Constable and Company first published Dracula in 1897 and reprinted it eight times over the next twenty-two years. Most subsequent editions of Bram Stoker's masterpiece have been copies from this edition, from the Doubleday edition of 1899, or from the Rider edition of 1912, which corrected many of the typographical errors that occur in the first edition.

Constable also published an abridged paperback edition of Dracula in 1901. However, this edition is virtually unknown today. Given the stature and popularity of Bram Stoker's novel, this can only be attributed to the fact that copies of the revised edition are as rare as autographed first editions of Dracula. This is unfortunate, for the abridged edition contains several points of interest. To begin with, Stoker himself made the revisions. He abridged the text by over 15% (from approximately 162,000 words to 137,000 words), deleting some of the lengthy descriptions and conversations which dominate the first edition, in order to concentrate on the action. He also made minor changes to the text. For instance, in Chapter X, Professor Van Helsing's cumbersome phrase: "make him kick the beam, as your peoples say" is replaced by the more straight-forward "outweigh him." Although some of the atmosphere of the original work has been lost, most authorities agree that the revised edition of Dracula is more readable and, hence, more enjoyable than the common, well-known text.

A republication of this classic work is long overdue. However, it should be noted that the text of the paperback edition was set in double columns of 6-point type, crammed into a mere 138 pages. Therefore, the present edition has been redesigned and retypeset. I have also taken the liberty of correcting obvious mistakes which were carried over from the first edition. Thus, in Chapter IV, the word "to" has been inserted in the sentence: "I have already spoken [to] them through my window to begin an acquaintanceship." In addition, the inconsistent spellings and typographical errors which plague the abridged edition have been eliminated. Finally, the cover of the paperback edition, which is one of the earliest and most memorable depictions of Count Dracula, has been reproduced as an enameled frontispiece.

I would like to think Robert James Leake of the Count Dracula Society for entrusting me with the copy of our favorite novel. His friendship and generosity have made this edition possible.

Robert Eighteen-Bisang

Introduction

It is a pleasure for me to introduce this marvelous reprinting of the 1901 edition of Dracula. The original edition of 1897 was abridged by the author, Bram Stoker, and published in April of 1901. It is republished her along with welcome corrections by Robert Eighteen-Bisang.

This book is important for various reasons. To begin with, the abridgment reads better than the original, well-known novel. This may seem odd, given the fact that Dracula is so popular that it has never been out of print. However, most scholars agree that Stoker's novel needs trimming; there are to many characters in it and too many obviously extraneous passages.

As strange as it may seem, Stoker's notes for Dracula (which are housed at the Rosenbach Foundation in Philadelphia, and are still unpublished) show that the author has originally conceived of an even longer and more convoluted story, with even more characters. How could a man who wrote such potboilers come along with a masterpiece of horror? No one knows. In fact, there are a number of legends about the actual authorship of the novel. H. P. Lovecraft, America's most famous fantasy writer after Poe, even suggested in an unpublished letter, located in the archives of Brown University, that some "old lady" who was offered the job of revising Stoker's Dracula manuscript in the early 1890s found it to be a "fearful mess" but Stoker did not like her price and found someone else who whipped the manuscript into such shape as it eventually acquires. However, in 1984, the discovery of the original Dracula manuscript with Stoker's own handwritten corrections and amendments on virtually every page, proves that he was indeed the author. Any other author would have sensed that the story is just too damn long, and cries out for abridgment. The First edition ran 390 pages, much shorter than Tolstoy's War and Peace, but still too long for a gothic thriller.

The context in which Stoker made his revisions is revealing. In 1898 a huge fire destroyed most of the sets and costumes at Henry Irving's Lyseum Theatre, where Bram was manager. The sixty-year-old Irving oscillated between severe depression and rage. So it was left to Bram to clean up the mess. In shouldering the burdens caused by this crisis, the physically exhausted Bram contracted a severe case of pneumonia, which took months to heal.

In 1900, between tours by Henry Irving's Theatrical Company, Bram Stoker and his wife, the pre-Raphaelite beauty Florence, stayed at a little hotel called the Kilmarnock Arms (which still exists) at Cruden Bay on the east coast of Scotland. Cruden Bay had become the Stoker's favorite vacation spot. This is where Bram put the final touches on the first edition of Dracula after seven years of serious research and writing. And it was also at Cruden Bay that he abridged the text. He cut some 25,000 words from the text of 1897 in order to accommodate Constable's sixpenny-paperback format, He wrote facing Slains Caste across from Cruden Bay village, one of the possible visual inspirations for Castle Dracula.

About one year after the publication of the abridged version of Dracula, the Lyceum Theatre fell into bankruptcy and was forced to close in July of 1902. After loosing his job as a theatrical manager. Bram, who had been only a part-time author, was forced to depend on the sale of Dracula, and other literary works for his livelihood. Unfortunately, his royalties did not make him a wealthy man.

A few of the main changes are worth nothing. For example, in Chapter I he leaves out the superfulous passage which contains the phrase "For the dead travel fast" ("Dem Die Todten reiten schell"), which is loosely derived from Burger's ghostly German love poem, "Lenore." In Chapter XII he omits the vignette about how Quincey Morris was attacked by a vampire bat in South America. But Bram did not make any major changes to the section dealing with the destruction of Lucy in her tomb (Chapters XV and XVI).. He must have realized that this one of the most powerful and well-written parts of the novel. Most films have retained this scene in their adaptations of Dracula. In fact it is one of the most compelling sequences in the most recent version, Francis Ford Coppola's eponymously titled "Bram Stoker's Dracula" (as if there were any other!).