CESNUR - Centro Studi sulle Nuove Religioni diretto da Massimo Introvigne

www.cesnur.org

www.cesnur.org

1. Senegal's Presidential Elections of 2012: Background and Results

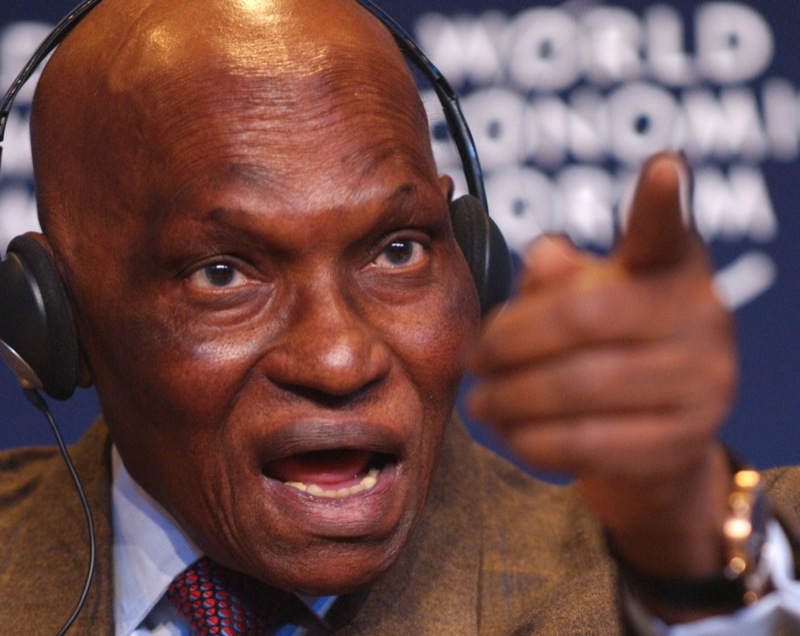

In February and March 2012 I went twice to Senegal, each time for eight days [0], in order to study the presidential elections [1], with a special focus on the role and influence of religious movements in the electoral process. The elections were characterized by a conflict, which in some regions escalated into actual violence, between supporters and critics of Abdoulaye Wade [2], the 86-year old leader of the Democratic Party of Senegal (PDS) who had been in office as president since 2000. Wade's electoral victory in 2000 ended forty years of Socialist presidents, first the Catholic poet Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906-2001), and then Senghor's right-hand man Abdou Diouf. Wade was initially genuinely popular, but in later years he was increasingly regarded as authoritarian and megalomaniac. The construction between 2008-2010 in Dakar of the African Renaissance Monument, Africa's tallest and biggest statue [3], was often perceived as evidence of his growing megalomania. Ironically, although Wade's party had a free market and anti-Socialist agenda, the monument was designed in North Korea and built by a North Korean company. Wade's attempt to nominate his son Karim as his designated successor also alienated those in the PDS who aspired themselves to the succession, including the president's brilliant right-hand man Macky Sall [4].

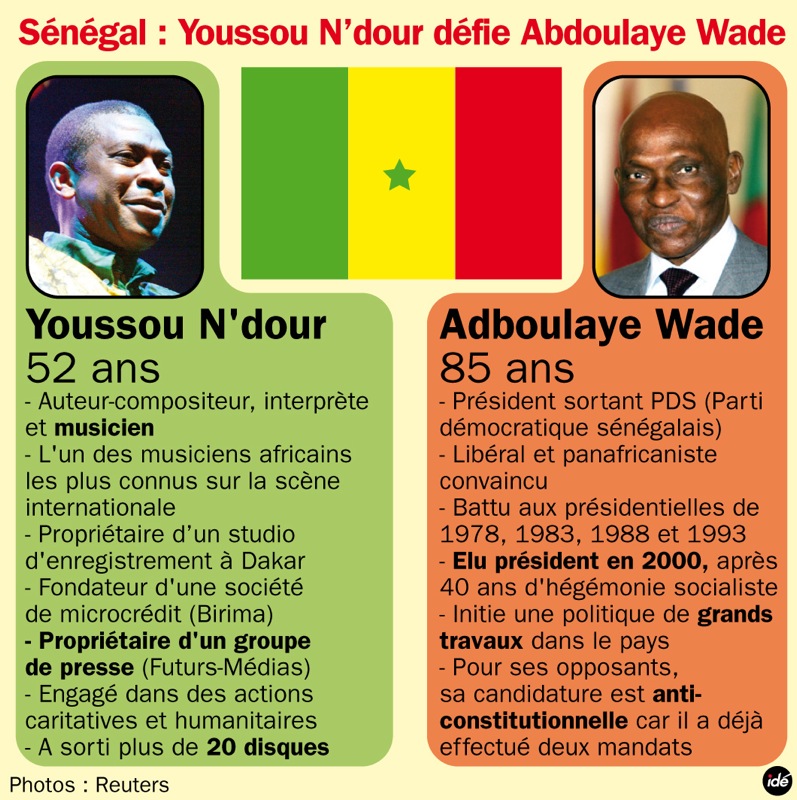

Tensions mounted when Wade, who had been elected in 2000 on a platform which included a limit of two terms for each Senegalese president, announced that the limit was not retroactive and will thus not apply to him, and that he will seek re-election for a third term. He also introduced a law granting to incumbent presidents seeking re-election the possibility of being elected directly in the first electoral round, provided that no other candidates has more votes and that they reach at least 25% of the total votes. Although the Constitutional Council validated Wade's bid for a third term, violent protests erupted. After the bloody protest day of June 23, 2011, Wade voluntarily withdrew the 25% law. Most of the 13 candidates opposing Wade in the 2012 election were part of a movement of protest named M-23 after the protest of June 23. The younger and more radical protesters, inspired by musician Youssou N'Dour [5] – who had been excluded from the list of presidential candidates by the Constitutional Council for lack of certain formal requirements –, joined the movement Y-en-a-marre ("I am fed up").

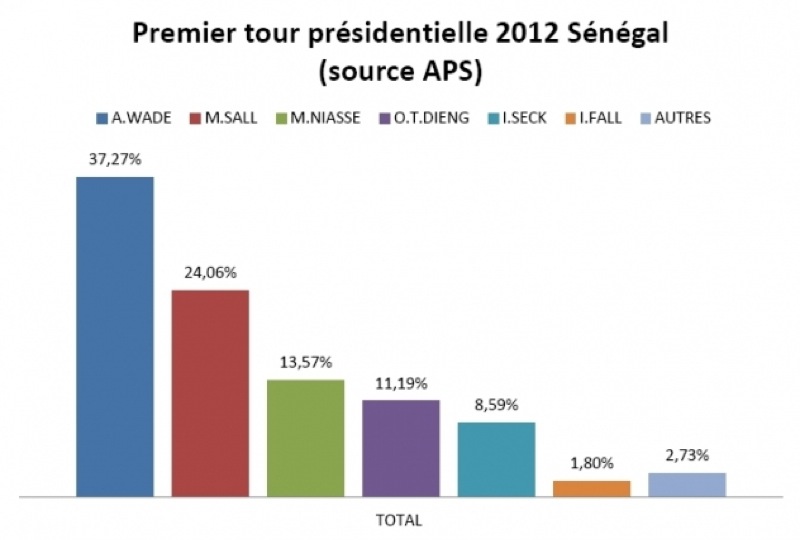

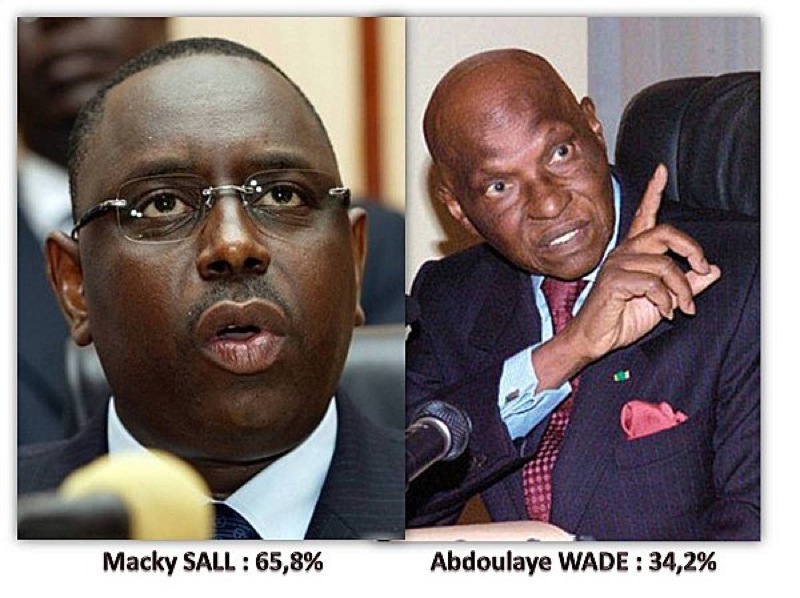

Both M-23 and Y-en-a-marre promoted massive rallies asking Wade to withdraw his presidential bid. Although a handful of protesters died, the president maintained his bid. The Socialist Party was weakened by the fact that it presented two rival candidates, and the former prime minister of Wade, Sall, emerged as the strongest alternative to the incumbent president. In the first round of the elections, on February 26, 2012 Wade received 34,8% of the vote and Sall 26,6% [6]. International observers noted some irregularities in favor of Wade, but these were not enough to elect him in the first round. There were widespread concerns that more irregularities may follow in the runoff election, and that Wade may proclaim himself the winner at any rate, thus precipitating the country into a potential civil war. In fact, the runoff of March 25, 2012 went on quietly, and Sall defeated Wade with 65,8% of the votes against the incumbent president's 34,2% [7]. Sall subsequently tried to include in his administration representatives of the more radical anti-Wade protest, appointing inter alia Youssou N'Dour as Minister of Tourism and Culture.

2. The Role of Religion in the Elections

Interestingly, both Senegalese and foreign media devoted a substantial coverage in the weeks preceding the elections to the role of religious movements. In order to understand why this happened, it is important to consider the general dynamics of religion in Senegal. 94% of Senegalese are Muslim. Senegal was not Islamized by military conquest, but through the activities of itinerant preachers, who gained favor in the courts of pre-colonial Senegalese kingdoms. All his preachers belonged to Northern African Sufi brotherhoods, and some of them founded new brotherhoods of their own. The French colonial power maintained a quite ambiguous relationship with the brotherhoods. In part, it courted them in order to gain their sympathy or at least neutrality in the face of anti-colonial uprisings. Those brotherhoods suspected of anti-colonial sympathies were, however, severely repressed. The French also favored the implantation in Senegal of the Roman Catholic Church, which was in general quite conservative and pro-colonialist. It is more than a coincidence than the key figure of the Senegalese Catholic hierarchy in the 20th century was the French archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (1905-1991), who was archbishop of Dakar between 1947-1922 [8] (although from 1947 to 1955, when the Dakar archdiocese had not yet been formally established, his official title was apostolic vicar), before leading an international protest movement against the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

The oldest Sufi brotherhood in Senegal, the Khadiriyya, went into some decline in the 20st century, leaving as the two main groups the Tijaniyya and the Muridiyya. Roughly 80% of the Senegalese population belongs to one of these two brotherhoods. In their strongholds in the suburbs of Dakar, the Layennes – part Sufi brotherhood, part new religious movement with significant departures from mainline Islam – constitute in turn a solid majority [9]. As for the Catholic Church, my fieldwork persuaded me that it went into a process of "brotheroodization". It includes less than five percent of the population, and it is widely perceived as the third (or fourth) great brotherhood. It is often expected that the Catholic bishops somewhat act as brotherhood leaders, offering economic help and political patronage to the faithful. Although the process is both acknowledged and resisted by the Catholic priests and bishops I interviewed, one advantage is that today Catholicism is rarely perceived as a foreign or colonial religion, and its relationship with the Muslim brotherhoods is quite good.

It is difficult to overestimate the pervasiveness of the brotherhood's influence on Senegalese life. Most businesses, shops, restaurants and even cars and trucks proudly display the brotherhood affiliation of the owners, and harbor the portrait of the brotherhood's local leader [10]: the "marabout", a word which is also used to designate folk healers, but in this case indicate members of the brotherhoods' hierarchies. I have also observed children collecting and trading cards of the marabouts just as European or American children collect football or baseball cards – although football cards do exist in Senegal too, and are sold alongside these of the marabouts [11].

But what about politics? I will shortly describe the attitude of the two main brotherhoods and the Layennes towards the 2012 presidential elections, and offer some conclusions.

3. Elections and the Brotherhoods: The Tijaniyya

Although roughly one of each two Senegalese belongs to the Tijaniyya, the fact that it is currently divided in six main rival branches weakens its political influence, or rather makes it more effective in local rather than in national politics. Traditionally, the Tijanis have been perceived as connected to the Socialist Party, although the first Socialist president, Senghor, was a Roman Catholic. One of the two Socialist candidates in the 2012 elections, Moustapha Niasse, is a member of the family controlling the second largest Tijani branch in Senegal, headquartered in the holy city of Medina Baye, a suburb of the Southern city of Kaolack [12]. Although the story of the Niasse family includes internecine struggling and schisms – the founding of Medina Baye is in itself the result of the separation of Ibrahim Niasse (1900-1975) from the group led by his father Abdallah Niasse (1840-1922) –, Moustapha Niasse won the elections quite easily in Kaolack – where I was during the first round [13] – and came out third after Wade and Sall in the national count, with 13,2% of the votes. Niasse also received, according to my informant, a fair share of the Catholic vote, although other Catholics favored Sall.

The main branch of the Tijaniyya in Senegal is led by the Sy family and is headquartered in the Western holy city of Tivaouane [14]. It is perceived as quietist, generally favoring the status quo. The French even constructed a pioneer railway station in order to facilitate the affluence of the green-dressed pilgrims to Tivaouane [15]. The Sy branch, however, was somewhat disturbed by Wade's very public affiliation with the rival Murid brotherhood. The relationship with the president went from bad to worse on February 17, 2012 when tear gas grenades thrown by the police against the anti-Wade protesters hit the main Tijani mosque in Dakar, El-Hadji Malick Sy [16]. When news of the incident reached Tivaouane in the same day, riots immediately erupted and the mayor's office was burned down. Wade quickly dispatched his Minister of Internal Affairs Ousmane Ngom to Tivaouane in order to present the government's excuses. The Minister, however, was surrounded by an angry mob and physically prevented from leaving Tivaouane, until he was finally liberated by the intervention of the police's special forces.

Not surprisingly, Wade received comparatively few votes in areas dominated by the Sy Tijanis. It came more as a surprise that, during the protests after the Dakar mosque incident, radical Salafist slogans were shouted, something quite uncommon in Senegal. Media showed some concern about possible "fundamentalist" infiltrations from abroad among the Tijanis, whose Islam is the most conservative among the Senegalese brotherhoods. In my fieldwork I found evidence of these trends in tracts distributed in Tijani centers accusing both the Murids and the Layennes of being non-Moslem polytheists, in calls to destroy the African Renaissance Movement because it exhibits "naked" women, and in a certain "cleansing" of Tivaouane book stalls by eliminating Tijani pamphlets from Guinea and other African countries about the interpretation of dreams and other quasi-magical subjects, normally regarded with suspicion by Salafist orthodoxy. These pamphlets were however liberally on sale around the main mosque of the Niasse branch in Medina Baye [17].

4. The Muridiyya

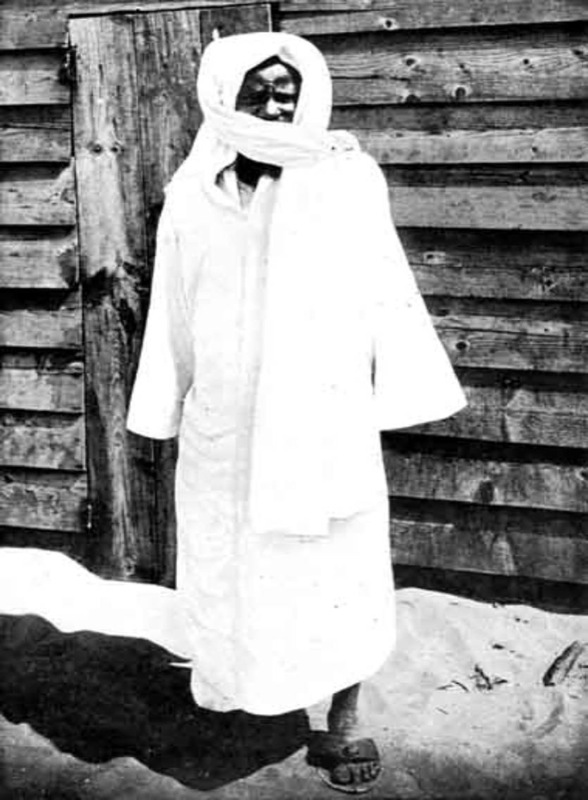

Although Murids constitute 30% of the Senegalese population, against the 50% of the Tijanis, the fact that they did not suffer significant schisms and their unique social structure make them both more visible and more politically influential in Senegal, and this is also true within the Senegalese diaspora in the U.S. and Europe. The Muridiyya brotherhood is an indigenous Senegalese creation, founded by Ahmadou Bamba (1853-1927) [18] at the end of the 19th century. Murids recognize as the birthdate of their movement the founding of the Holy City of Touba in 1887, which marked the final separation of Bamba from the oldest Muslim brotherhood in Senegal, the Khadiriyya, where both his parents were active. The French were quite suspicious of Bamba, and exiled him repeatedly to Gabon, Mauritania, and to the Senegalese city of Djourbel, which thus became the second holy city for the Murids [19]. In the end, they came to term with a movement they were not able to destroy, and in 1926 even awarded Bamba the Legion of Honor, the highest decoration in France.

The originality of the Muridiyya [20] [21] lies in the bai'a, a contract the member of the brotherhood, or talibé, signs with his marabout, promising him the kidma, of service, which consists in contributions both in kind, by working for the marabout, and in cash. The marabout in turns promises to advise the talibé in spiritual and social matters, and to pray for him. In time, the bai'a system became both extended and complicated. The bai'a has been particularly studied by Italian sociologist Ottavia Schmidt di Friedberg (1957-2002), who challenged the idea that it amounts to simple exploitation of the talibés by the marabout (Schmidt di Friedberg 1994).

Influential marabouts often guide extensive international economic networks, involving thousands, and in some exceptional cases even millions, of talibés, providing inter alia the main services needed by Senegalese immigrants overseas. Local marabouts in Murid rural villages often distribute the croplands among the villagers. Members of the Bay Fall, a movement within the larger Murid movement, founded by Bamba's close associate Ibra Fall (1858-1930) [22], are specially devoted to their marabouts, and often act as bodyguards for members of the Murid hierarchy.

Often accused of nurturing a non-Islamic personality cult of Bamba and his successors in the role of caliph general, all members of Bamba's Mbacké family, since the times of the leadership of caliph general Abdoul Ahad Mbacké (1914-1989) in the 1970s the Murids tried to reform and mainstream themselves into an Orthodox Sufi order, and to establish relations with internationally respected Muslim bodies. The peculiar social system of the Murids is particularly well suited to a widespread political influence. Although occasionally denied, the electoral influence of the marabouts on their talibés is quite obvious. Distinctions between religion and politics seem to be non-existent in the holy city of Touba. Anti-Murid books and even cosmetics regarded as unfit to an Islamic woman's modesty are burned in public with the participation of both religious and civil authorities (see Diagne 2008). On the other hand, Murid marabouts are often regarded as playing a useful role in areas and regions of Senegal where the presence and effectiveness of the state is minimal.

The political influence of Murid marabouts became a hotly debated issue in the 2012 presidential elections. Both candidates in the runoff, Wade and Sall, were Murids. While Wade, however, had always been quite vocal in his Murid identification, styling himself as "the first president-talibé" [23], Sall maintained a more cautious attitudes, praised French-style separation of religion and state, and created widespread controversy by a remark during the campaign that "marabouts are citizens like everybody else". Murid hierarchies reacted to the remark by cancelling a meeting scheduled in Touba between Sall and the Murid's current caliph general Sidy Mokhtar Mbacké. Interestingly, Sall was then praised and very publicly received in Tivaouane by Mbaye Sy Mansour, leader of the Sy branch of the rival Tijani brotherhood [24]. Sall then tried to appease the Murids stating that his comments had been misinterpreted and that he remains a loyal Murid and "a talibé". But tensions remain even after Sall's victory. When the newly elected president finally visited Touba on July 25, 2012, he inclined himself devoutly to receive as a talibé the caliph's customary benediction [25], but was also told that his delayed arrival to the meeting has been perceived as disrespectful.

5. Anti-Cultism, the Elections and the Béthio Thioune Movement

Electoral controversies about religion largely centered on the role of Béthio Thioune [25b], perhaps the most influential Murid marabout after the caliph general. Thioune, who claims more than four million talibés, was a close associate of Saliou Mbacké (1915-2007), the last surviving son of Bamba to serve as caliph general. Saliou was succeeded in 2007 by Mouhamadou Lamine Mbacké (1925-2010), the first Murid caliph general who was a grandson, rather than a son, of Bamba. When Saliou died, Thioune refused the formal act of allegiance to his successor Lamine, while stating that he obviously recognized him as the new legitimate caliph general. Thioune however claimed that he maintained a direct spiritual relationship with the deceased caliph general Saliou, who kept appearing to him in mystical experiences and dreams. This internecine tension among Murids acquired a political meaning during the 2012 elections. While the new caliph general and Lamine's successor, Mokhtar, refrained from publicly endorsing Wade with a formal recommendation (ndigël), although certainly he did nothing to stop the quiet propaganda for the incumbent president going on in many Murid mosques, Thioune claimed that the spirit of the deceased caliph Saliou had appeared to him and stated unequivocally that all Murids should vote for Wade.

After Sall's victory, Thioune realized he was in deep trouble. Although he quickly congratulated the new president and described Sall as a good talibé, the pro-Sall media started labeling Thioune as a cult leader, with a language often borrowed from the French anti-cult movement. The marabout was also widely criticized for living quite publicly with seven wives, three more than the maximum number of four wives allowed by Islam [26]. Clashes erupted in April 2012 between Murids favorable and hostile to Thioune. In the weekend of April 21-22 two of Thioune's talibés were killed [27]. Thioune allegedly ordered that they should be rapidly buried without reporting the incident to the authorities. He was arrested on Monday April 23 and charged by a court in Thiés on April 26 along with twenty of his disciples. The court also ordered Thioune to remain in jail while awaiting the process. Although Thioune was granted the best possible conditions in jail, and was allowed to receive 1,500 followers each week there, protests against what was perceived by the marabout's talibés as a political frame-up continued throughout the country [28]. In the parliamentary elections of July 1, 2012, the marabout's son Khadim Thioune was elected as a member of the parliament, and quickly started a political campaign for the liberation of his father, who at the time of this writing (September 20, 2012) remains in jail in Thiés.

6. The Layennes

Layennes represent only 2% of the total population of Senegal, but they are concentrated in a handful of municipalities in Greater Dakar, where they exert an influence amounting to virtual political control (Diagne 2008). Seydima Limamou Laye (1843-1909), a poor fisherman from the village of Yoff, experienced a mystical vision after his mother died in 1884. He claimed to be the messiah, the Mahdi, and the second coming of Muhammad (ca. 570-632), who came first to the Arabs and the Europeans and now was coming to the Africans [29]. Violent opposition to these claims [30] induced Limanou to move to a new holy city of Cambérène ("the first Cambérène", later called Ndingala) [31], where phenomena associated with the water of a miraculous well [32] attracted many followers. Limanou died in 1909 [33] and was succeeded by his son Seydina Issa Laye (1876-1949), who proclaimed to be the second coming of Jesus just as his father had been the second coming of Muhammad [34]. Issa also assumed the title of first caliph general of the Layennes, and built a mausoleum for his father in Yoff. When the first Cambérène was hit by a severe plague epidemic, Issa moved to headquarters to a newly built "second Cambérène", where he was buried after his death in 1949 [35]. Most of Cambérène's present 41,000 inhabitants are Layennes.

Widely accused of being a non-Moslem cult, the Layennes sought legitimacy in the 1980s under their third caliph general Seydina Issa Laye (1914/1915-1987) by emphasizing Shia influences on their founder and establishing contacts with Iran. Later, under the fourth caliph general Mame Allassane Thiaw Laye (1917/1918-2001), the Layennes insisted on their being Orthodox Sunni Muslims, a claim strongly disputed by some Tijanis but accepted by the Murids, with which the Cambérène movement forged a political alliance. Relationships with the Murids were helped by the fact that the fifth and current caliph general, Abdoulaye Thiaw Laye, had served in the army with the Murid president Wade, and remained his good friend.

Wade, however, fell into disfavor with the Layennes when Dakar's new sewerage system, otherwise hailed as a significant success of the president, started discharging the capital's polluted runoff near the movement's headquarters in Cambérène [36]. This led the Layennes both to establish a number of organizations aimed at raising ecological awareness in Senegal and to vote largely for Sall, who promised to take care of the sewers problem, although how this could be done remains unclear to this date.

Conclusions

A common reading of the 2012 presidential elections is that they represented a step in the secularization of Senegalese politics. Although Wade was vocally supported by Thioune, until the election the country's most prominent marabout, and favored by a majority of Murid leaders, in the end he failed to win his re-election. While this view was quite prevailing in the Western and some Senegalese media in the aftermath of Sall's victory, my own fieldwork and interviews allow for an alternative view.

An interesting point concerns anti-Masonism. Freemasonry in Senegal has been popularly perceived as a movement of Westernized elites. favoring firstly French colonial power and then the interests of large transnational companies. Both leaders of the Sufi brotherhoods and the Catholic Church have been among the most vocal critics of Freemasonry. Both candidates in the runoff accused each other of being a Freemason [37]. Actually, Wade had been described as such in the French media, and replied by an official note explaining that he became curious about Freemasonry and was initiated in Besançon, France, when he was a university student in 1959, then realized that his ideas were quite far away from the Freemasons' and resigned after a few months ("Sénégal: Wade a été franc-maçon" 2009). Wadists in the 2012 campaign pointed out that, if anything, Sall's comments praising French separation of religion and the state were much closer to the Masonic ideology. Be it as it may be, the controversy about Freemasonry showed that the two candidates were quite well aware of the role religious anti-Masonism may play in the elections.

Wade's presidency was characterized by what can be defined as a sustained celebration of Muridism as Senegal's national form of Islam. Although it is certainly true that the Muridiyya is the most influential religious group in Senegal's economy and politics, it should not be forgotten that 70% of the Senegalese population is not Murid, and that the total membership of the different Tijani branches fairly exceed the number of Murids. Wade's publicly exhibited Muridism increasingly disturbed both the Tijanis and the small but culturally influential Catholic minority. It is not impossible that it also disturbed some members of the Murid hierarchy itself, who resented Wade's friendship with the powerful but controversial marabout Béthio Thioune, and more generally preferred to exert their social hegemony less publicly and to maintain the best possible relationship with the other brotherhoods.

Crucially, what some perceived as Wade's aggressive form of political Muridism led the Tijanis, who represent half of the Senegalese population, to a closer involvement in politics in opposition to the incumbent president. Sall himself both cultivated the Tijanis and was careful to repeat that, certain political divergences with some leading Murid marabouts notwithstanding, he remained a devout Muslim and a loyal Murid talibé. Even the obscure incident leading to Thioune's arrest and prosecution should not necessarily be read as an assertion of the secular courts' authority over the Murids, since it is also part of an internecine religious struggle within the Murid community itself, a rather typical controversy opposing the institutional authority of the caliph general to the charismatic authority of an immensely popular preacher.

Perhaps, rumors of the death of Senegal's traditionally close alliance between religion and politics are quite premature. The 2012 elections did not mark the end of this alliance, but rather its reshaping and modernization, while the system of social and political influence by the brotherhoods [38] remains a distinctive feature of contemporary Senegal.

References

Diagne, Mountaga. 2008. Décentralisation et participation politique en Afrique : le rôle des confréries religieuses dans la gouvernance locale au Sénégal. Alliance de Recherche Université- Comunauté (ARUC) - Innovation Sociale et Développement des Communautés (ISDC), Ottawa.

Schmidt di Friedberg, Ottavia. 1994. Islam, solidarietà e lavoro. I muridi senegalesi in Italia. Torino: Edizioni della Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli.

«Sénégal: Wade a été franc-maçon». 2009. Le Figaro, 5-2-2009.

img src="el-mi-27.png" width="800" height="768">

img src="el-mi-27.png" width="800" height="768">